|

The second edition of the Endless Mountains Adventure Race, the only US-based qualifier for the 2023 Adventure Racing World Championship, kicks off today in northern Pennsylvania. The event, presented by Rootstock Racing, takes teams on a journey highlighting the rich environmental and industrial history of the Pennsylvania Wilds region, and there is perhaps nothing that better illuminates those connections than the start line of this year’s race: the Tioga-Hammond Dam. Constructed in 1978, the dam blocks the Crooked Creek and separates the Tioga and Hammond reservoirs. On Stage A, presented by Micro Rafting Systems, racers will travel by foot and packraft in, above, and along the creek and lakes, collecting eleven checkpoints along the way to TA 1, six of which are mandatory. Thanks to the enthusiastic support of the Army Corps of Engineers, teams will have the opportunity to portage directly over the dam and take in the dramatic, humanmade gorge that separates the two lakes. The stage ends at the Lambs Creek boat launch, where racers will pack up their rafts and set off by bike for Stage B. Stage B, presented by Crooked Creek Campground and Crooked Roots Adventures, is the most diverse leg of the race, offering teams a dose of multisport adventuring at its finest. They will start with a ride through the forest roads of Tioga State Forest. At Fall Brook, they will drop their bikes for the first of two embedded sections: a foot loop that includes a visit to the striking Fallbrook Falls. From there, they continue riding through a maze of ATV trails and single-track, which drops into Sand Run Falls and then up through picturesque downtown Wellsboro. While straightforward enough on the map, some teams may find themselves wandering a bit here as the race’s characteristic tricky navigation kicks in, especially after the Fall Brook foot loop. In Wellsboro, racers will encounter a mandatory media stop at the Penn Wells Hotel. There, Brian Gatens, host of The Dark Zone: An Adventure Racing Podcast, will interview each team for five minutes. When they leave the hotel, they will continue by bike toward the old Hesselgessel Quarry, built upon a former indigenous burial ground. James Hesselgessel disappeared in the 1860s, and soon after his quarry became inactive. But rumors continue to circulate of ghostly activity in the area on warm summer nights… Racers will drop their bikes near Hesselgessel for the second embedded loop – a trek to Blue Run Rocks for some scrambling and time on rope. Here, teams will encounter four top-roping routes in a playground of boulders, crevices, and small cliff faces, set and staffed by Crooked Roots Adventures. Each racer must complete at least one climb in order to avoid a time penalty, before continuing onto TA 2 via a route that will require sharp attention to the maps. A lucky few will arrive at the transition, at a sweeping overlook at Colton Point State Park, in time for sunrise on Day 2.

its adjacent trails served as a critical travel route into the 1800s, linking the Great Shamokin Path and Iroquois territory along the Genosee River. The development of the railroad and the growth of the state’s lumber industry disrupted the natural landscape and forced the indigenous communities to relocate. In the twentieth century, the forest service spearheaded efforts to rehabilitate the flora and fauna of the region. As teams trek through the rugged terrain, they may catch glimpses of bald eagles soaring overhead and river otters floating down the shallow creek. This edition of the Endless Mountains is nicknamed “The Grand,” and racers will find out why on Stage C, presented by Garmin. This stage takes teams on a point-to-point trek through the sculptured landscape of the Pine Creek Gorge, the so-called Grand Canyon of Pennsylvania. Known by the Seneca nation as the Tiadaghton Creek, the waterway and its adjacent trails served as a critical travel route into the 1800s, linking the Great Shamokin Path and Iroquois territory along the Genosee River. The development of the railroad and the growth of the state’s lumber industry disrupted the natural landscape and forced the indigenous communities to relocate. In the twentieth century, the forest service spearheaded efforts to rehabilitate the flora and fauna of the region. As teams trek through the rugged terrain, they may catch glimpses of bald eagles soaring overhead and river otters floating down the shallow creek. With a reclaimed rail-trail along the creek, spectacular waterfalls in the deep gorges that drop down into the Pine, a long-distance hiking route in the West Rim Trail, and a maze of mapped and unmapped trails on the plateau above, the Gorge is a gem of an outdoor playground. Unfortunately, during the summer months, water levels are too low for paddling, but adventure abounds nonetheless, and teams will have a unique challenge of navigating part of the stage using only written instructions and distance estimates. This section ends at Rattlesnake Rock, where teams will retrieve their bikes and head out on Stage D, presented by the Clinton County Visitors Bureau. During this relatively short ride, racers can let their feet recover and put their navigational chops to work, as they explore the beautiful Cedar Run Valley on their way to the Cedar Run CCC Camp, which operated from 1933 to 1941. There, under the direction of Lieutenant J. Wickerling, workers were tasked with planting trees, fighting forest fires, and building miles of roads and trails in Tioga State Forest, the great outdoors serving as a salve to the pains of the Great Depression. From the camp in Leetonia, mapwork will get interesting, with a variety of feasible routes connecting to the old rail grade that serves as part of the Midnight Madness bike race. Dot-watching should be exciting for this part of the stage, which ends at TA 3 in Ole Bull State Park. Here, racers will be treated to hot food as they prepare for the Stage E, presented by the Lumber Heritage Region, the crux of the race.

Cross Fork tributary, home to one of the biggest rattlesnake roundups in the country. Not to worry, though: the snake-hunters will be long gone by the time Endless Mountains racers pass through. The 2023 roundup took place while racers were checking in last Sunday…

This massive stage – projected to take top teams upwards of thirty hours – ends at Kettle Creek State Park, the best spot for elk encounters on this year’s course (especially for short-course teams that might elect to approach the next transition area from the north, along Kettle Creek Rd). Encompassing the middle third of the course, Stage E will likely shake up the race for a number of teams. The trek is roughly broken into thirds; the middle of the stage is rogaine in nature, with more linear routes on the front and back ends. Teams will have to strategize how many of the optional checkpoints to commit to, and many may find themselves going for 24-36 hours without seeing another person. How teams cope with sleep strategy, fatigue, nutrition, and sore feet will be a more significant factor than the 40+ miles and extended stretches of bushwhacking that they will encounter. After a long day on their feet, teams should enjoy Stage F, presented by the Clinton County Visitors Bureau, a pleasant ride out of Kettle Creek State Park and then a short, punchy climb up into the Whiskey Springs ATV trails for a sixteen-point mountain bike-o. All checkpoints here are optional, and dotwatchers should expect to see some interesting squiggly lines on the map as tired navigators work to stay oriented in the labyrinth of trails and checkpoints. While the area is well mapped, there are plenty of route options and rogue ATV trails that can make for some more complicated routefinding. Teams inclined to bypass the challenge, or those who are up against the clock, can save a few hours or more by pedaling along the West Branch Susquehanna to the boat put-in in Renovo, where the full-course and short-course routes converge for Stage G, presented by Micro Rafting Systems. The West Branch, meandering for 243 miles, bubbles up in the Allegheny Mountains and zigzags through central Pennsylvania. The region’s earliest recorded inhabitants were the Susquehannock people, drawn to the river’s drainage basin and the steep valley’s rich hunting grounds. Until the early nineteenth century, the river provided the main canoe route connecting the Susquehanna and Ohio Valleys. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the West Branch carried timber to the many mills lining its bank. At the height of the timber industry, these mills produced 5.5 billion board feet of lumber. In the 2022 Endless Mountains, racers took on a particularly bony stretch of the river to the northwest. This year, teams will take to the West Branch once again, but they should encounter a decidedly less frustrating float. On their thirty-mile journey, they will pass under the Hyner Hanglide Launch, where lucky teams may see adventurers of a different sort sailing overhead. They will also paddle by the Red Hill archaeological site, where in 1993 paleontologists excavated fossils dating back 365 million years. While there are no checkpoints along the way, giving teams a break from some unrelenting navigation, the real challenge will be contending with fatigue. If teams have managed their sleep well leading up to this stage, they should enjoy the steadily moving river paddle. If they didn’t, this relatively straightforward stage could become a nightmare of a different sort, as racers contend with prehistoric hallucinations on their approach into Lock Haven and the final transition of the race. In the early eighteenth century, members of the Anabaptist church arrived in Pennsylvania, escaping the religious persecution they had experienced in Europe. The state’s Amish population grew exponentially in the three centuries that followed, now numbering nearly 90,000. In Stage H, presented by New Trail Brewing Company, teams will encounter this lived history as they ride through the Loganton Valley, where in 1972 an Old Order Amish community settled. From Loganton, teams will climb up into Bald Eagle and Tiadaghton State Forests, enjoying the quiet calm of the gravel roads, some final route choice and navigational decisions, and unique historical ruins, before descending through the Mosquito Valley and into the bustling downtown of Williamsport for the finish line of the 2023 Endless Mountains Adventure Race.

0 Comments

Thirty-three teams will line up at the start of the second edition of Endless Mountains Adventure Race next week, the only US qualifier for the 2023 Adventure Racing World Championship. Seventy percent of the field is returning from the 2022 Endless Mountains, including reigning champions Bend Racing and runners up Rib Mountain Racing. Those squads, along with Bones Adventure Racing, who had to drop out last year due to injury, will all be vying for the podium. The Bend squad is entirely different from 2022, but certainly no less capable. Alex Provost, Karine Corbeil, and Jean-Yves Dionne hail from Quebec and will be comfortable on the east coast terrain. They are joined by one of the elder statesmen of the Bend squad, Dan Staudigal of Oregon. On Rib Mountain Racing, Tim Buchholz and Anna Nummelin return for a second year, joined by Jarrod Shoemaker, 2009 ITU Duathlon World Champion, and Joel Ford, who won the 2018 USARA Championship as part of the Rootstock Racing team. For Bones, Roy Malone and Mari Chandler are likewise returning; they welcome longtime teammate James Galipeau and Jesse Tubb, who was also part of the 2018 USARA nationals-winning team, to their Endless Mountains squads. Both Tubb and Ford are local to the Mid-Atlantic race scene, bringing valuable experience and muscle memory for this navigation-heavy event.

veteran expedition racers in Scott Ford, who raced on the second-place team at 2019’s Eco-Challenge Fiji, and Pete Cameron and Leanne Mueller, both now living in the foothills of the French Alps. They are joined by ace paddler Angus Doughty. There are several more US teams who will no doubt have their eyes on mixing it up in the top five. Keep an eye on No Complaints, featuring Doug Ritzert, Brandon Hopkins, Jennifer Debruyn, and rising star Amanda Bohley, as well as Chris Von Ins, Michele Hobson, Earl Blanchard, and Susan Alderman of Team Checkpoint Zero, racing in memory of their longtime teammate and expert navigator, Peter Jolles. Jolles passed away in a packrafting accident last summer, the same week that the inaugural Endless Mountains Adventure Race took place. Noticeably absent from this list is Team Untamed New England/VERT, who recently had to withdraw from the event due to injury. Rootstock Racing events are known for technical navigation, and Endless Mountains is no exception. Unlike many traditional multi-day adventure races that use checkpoints to curate an expansive journey, Endless Mountains offers racers the chance to test the limits of their map skills, requiring near constant route choice and precision navigation. Paraphrasing Lars Bukkehave, part of the 2022 winning Bend Racing squad, there are no ‘gimme checkpoints.’ The focus and attention to detail is unrelenting. I loved it. This unique style will certainly privilege racers with experience in the dense forests and more subtle terrain of the northeastern United States, and there are a number of such teams that will no doubt be ready to capitalize on any mistakes at the top of the field to climb in the standings. In this group, teams to watch include Adventure Addicts Racing, Only Mostly Lost, and Wildlings, all seasoned teams who are known for executing smart and strategic race plans. Adventure Enablers, with three racers returning from 2022, has had a breakout 2023 season so far, and they likely also come into this event with high ambitions. Finally, Team ThisAbility is no doubt looking to play spoiler, particularly against the likes of Adventure Addicts Racing, whose roster for this event includes Chip Dodd, co-captain of the ThisAbility squad. In the all-male division, expect to see Adventure Enablers/Enabled Tracking, Trust the Compass, and Chaos Required pushing the field early. All three include racers who completed the 2022 edition of Endless Mountains. In Trust the Compass, Jason Glenn and Jason Madey are joined by Jared Krefski and Kristian Randt, both longtime participants in shorter events whose performance has elevated considerably in recent years. Other returning teams in this division include Skills Optional Racing and Edge of the Wild, both of whom successfully completed the 2022 course. This division is rounded out with Blazing Paddles, traveling to Pennsylvania from the southeast, and Up Hill Both Ways, crossing the border from the Ontario area. There are two all-female teams lining up at the start: BiPolar, named for their cross-hemispheric origins, and Ubuntu, a word and African philosophy that translates both as “humanity” and “I am because we are.” In addition to demonstrating creativity in their team names, the women that comprise these rosters bring deep experience in endurance pursuits and strong team dynamics, creating for prognosticators an exciting degree of uncertainty in predicting a winner.

rivaled only by Team Gung Ho, also in this division. Jay and Penny Zech, owners of Gung Ho Bikes in York, PA, along with longtime teammate Kevin Lint, collectively bring decades of racing to the course, and a well-honed sense of humor to accompany that experience. They are looking to improve upon their performance in 2022 and should definitely be taken seriously.

This year’s team list also includes a mashup of several rosters from the 2022 edition – including The NorthStar, GOALS ARA Masters, and 5060 Adventure, all with plenty of experience to successfully negotiate this course – and a number of racers stepping up to the multiday distance for the first time. Watch 3ROC AR, Bluebolt/Rockhop Racing, Epic Nav, Moonhowlers, Texas Pride, Two Thorns and Tenderfoot, and Who Dis tackle the challenges of expedition racing with the grit and grace emblematic of so many adventure racers. The 2023 Endless Mountains Adventure Race begins Monday, June 26 at 10:00am EST. For more information, visit the Endless Mountains website. During race week, you can find expansive coverage here. Live tracking, presented by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, is available here. Thirty-two teams will line up at the start of the inaugural Endless Mountains Adventure Race next week, a Demonstration Race in the 2022 Adventure Racing World Series season. The field, the largest among North American ARWS events this year, represents a wide swath of the US adventure racing community, with a few international racers on the line as well. At the pointy end, expect to see the veterans of Bones Adventure Racing and Bend Racing mixing it up for the top of the podium. The Bones roster includes Roy Malone; Chad Spence, fresh off Expedition Croatia; Charles Triponez; and Mari Chandler, who recently raced with Team Vidaraid for the win at Expedition Oregon. On Bend Racing, Jason and Chelsey Magness are joined by Lebn Lovejoy and Lars Bukkhave. Lovejoy and Bukkhave both retired early from Expedition Oregon last month and are likely hungry for redemption. Chelsey Magness, meanwhile, recently won the WEMBO 24-hour mountain biking world championship.

Other teams to watch include Untamed New England, with Erik Grimm, Michelle Hobson, Dave Lamb, and Jason Urckfitz; No Complaints, with Sara Dallman, Shawn Lemaster, Eric Olsen, and Doug Ritzert; and Rootstock Racing, with Andy Bacon, Michael Dickey, Kristin Eddy, and Mark Lattanzi. These three teams bring with them strong navigational chops, and they are capable of racing fast and strategically. They are also familiar with the challenging Pennsylvania terrain and the technical navigation emblematic of Rootstock Racing events. Finally, keep an eye on Strong Machine Adventure Racing. Lead navigator Glen Lewis cut his AR teeth in the PA woods, and the team has been training hard and racing well in preparation for this event. In the all-male division, Rival Racing and Team Deviate look to push the pace early, and Adventure Enablers and Chaos Required both have the legs and the mapwork to vie for the podium. Rival Racing is new to multiday adventure racing, but the team has a strong athletic pedigree and they have been asking all the right questions leading up to the 2022 Endless Mountains. Team member Jason Glenn was born and raised in Clarion, PA, host site for the race. Kevin Poirier and Mike Garrison of Team Deviate, meanwhile, are coming off a fifth-place finish at Expedition Oregon (with Urckfitz of Untamed New England). Both are well trained and experienced at the multi-day distance. This is Garrison’s second of three ARWS events this summer.

Pushing them will be Team Wildlings, a collection of seasoned expedition racers with strong biking legs and excellent map skills. The team includes former pro soccer player Kathy Hoverman and former pro canoe racer Brenda Carlson-Brown. Their grit, combined with Shelley Johannesen’s training base – fresh off Expedition Oregon (with Lattanzi from Team Rootstock Racing) and a multi-week hiking trip in Tibet – and Barbara Niess-May’s navigational prowess make them a team to watch. The all-women’s field is rounded out with Masters in Age Only. Diana Driscoll has twenty years of adventure racing experience – largely in Pennsylvania – to draw from during the event, and Donna Boots has racked up more endurance events in her short career than many racers will in a lifetime. Joining them is Megan Moir, new to expedition racing but eager to work with her teammates to get through the course together. Moir’s secret weapon is Biltong, a South African jerky sure to fuel her through five days in the PA Wilds. The 2022 Endless Mountains Adventure Race begins Monday, June 20 at 10:00am EST. For more information and link to live tracking, visit the race website. During race week, follow along on facebook and instagram. In our final edition of the Expedition Playbook, we cover the ever-elusive topic of nutrition – or, to be more precise, race-day(s) nutrition. If we’re being honest, we thought about sidestepping nutrition entirely. Perhaps more than any other topic we’ve discussed in this series, race nutrition is probably the most varied and personal issue in our sport. Talk to ten racers, and you’ll find ten different strategies for fueling during an event. That said, keeping yourself fueled and hydrated is directly linked to your ability to reach the finish line and meet your race goals, and we would be remiss not to unpack it just a bit. Let’s begin with what you won’t find here:

philosophies of race nutritionTalk to a room of adventure racers, and – broadly defined – you’ll generally find four, sometimes overlapping, approaches to race nutrition.

general tipsWhile there are endless approaches to race nutrition, we find that there are some tried-and-true strategies that reach across almost all teams. Here they are, in no particular order:

And that’s a wrap for the Endless Mountains Expedition Playbook. Train race, prep smart, recover well, and we’ll see you in the woods! A decade ago, few adventure racers had ever seen a packraft, and many had not even heard about the sport that traces its roots back to Alaskan backcountry exploration and the famous Alaskan Mountain Wilderness Classic. In the ensuing years, the sport has taken off and is now commonplace in many expedition-length events in the US. Even shorter events are beginning to integrate packrafting into their courses. Along the way, there has emerged a cottage industry around the sport, with multiple companies producing great boats to match different price points and many outfitters offering rental service to racers and adventurers alike. Unlike other equipment, investing in a raft can be intimidating: compared to bikes, headlamps, or other standard items found in a gear closet, it can be hard to test out packrafts or even get your hands and eyes on them to assess them before laying down the credit card. In this edition of the Expedition Playbook, we aim to offer guidance on some of the basics, but we will not be dissecting nuances like seats, materials, gear storage, and inflators (manual and electronic; yes, there are electronic inflators teams are using). For more information on some of these details and more (including DIY options), check out this article. And as always, ask around. Many experienced racers have invested in boats at this point, and most have experience with different brands. Online reviews can be helpful, but beware: many packrafters are not racing with their boats, so what might work for the average rafter might not translate well to AR and racing. Before we dive in: one elephant in the room: WHICH raft should we buy? We will save specific recommendations for the end of the article, but here are some considerations worth exploring. costPerhaps the number one question that comes up for the new packrafter is: how much money do I need to invest in this equipment? It’s a fair question, and even cheaper packrafts can carry a degree of sticker shock, as they will still run you at least several hundred dollars. Some considerations:

So… what about the cheaper boats? Are you saying I have to shell out four figures for a boat? Not necessarily. Consider the following, and if you can check off these boxes, then you might be fine with a more affordable option.

Two further considerations as you decide whether and how to invest in rafts. First: many seasoned racers started their packrafting careers in more affordable boats, convincing themselves (and being convinced online) that there isn’t much difference between lower-end and higher-end brands. Often, these racers ended up reinvesting in new rafts within one or two races, after seeing how different they actually perform on the water. If you have plenty of disposable income, maybe this isn’t a big deal, but investing in a $500 boat only to go out and buy an $800-1000+ boat within a year or two is a bummer. Second: Especially in day-long events, you’ll see some teams invest in what literally might be a pool toy. Odds are good that this isn’t what race directors had in mind when they were designing the packraft section of their race. If it happens to be a relatively superficial and short section, you may be able to get away with a $40 beach raft from Amazon, but more likely than not, your experience probably won’t end well. doubles vs singles Another common question that comes up: do we buy a tandem raft or a single

Of course, all races are different, and unless you really are a gear junkie, you probably aren’t going to invest in multiple rafts for different conditions (though many experienced racers do, over the course of several years). Some additional general considerations:

*Expedition Oregon is the clear exception to these norms. The race often includes more technical paddling. It’s safe to assume that teams you should be more prepared for this race than most, and if there is ever a time to consider extra gear like spray decks, it’s here. TrainingIf you have considerable paddling experience, transitioning to a packraft may be relatively straight forward. They will handle differently than kayaks and canoes, but you will likely be able to adjust using your experience quickly enough. Even then, it is valuable to seek out instruction and guidance from experienced packrafters. And if you are jumping into packrafting without much paddling experience, you absolutely should consider some training. In the Northeast, Eric Caravella recently started Packrafting Adventures. Training like this is invaluable, and Eric is offering discounted rates to registrants of a number of adventure races that are including packrafting in 2022, including the Endless Mountains. Reach out to us or to Eric for details. While packrafting is still a fledgling discipline under the American Canoe Association, a growing number of instructors often are able to set up courses for teams or small groups if there are no available classes. the goodsOK. “Just tell me what to buy,” you say. We’ll begin at the beginning: the history of adventure racing, in the USA at least, has long been intertwined with Alpacka Raft. For over a decade Alpacka dominated the packrafting industry. There were a few other companies offering more affordable options that some swore performed nearly as well. They didn’t. In these boats racers often encounted torn-out bottoms, ripped seams, poor tracking, and heavier weights (while still being more damage-prone). In short, no one could hang with Alpacka. In recent years, however, a number of new and exciting options have hit the market, which has opened up all sorts of new, and more complicated, decisions for adventurers. In 2022, you will see a more diverse array of packrafts at any given race, even among the more competitive and experienced teams. For one summary of some of the recognized brands, check out the relevant section in this article. At Rootstock Racing, we are excited about our new partnership with Microrafting USA. MRS packrafts have cemented themselves as a go-to raft on the international racing scene; many elite racers in the South Pacific, Asia, and Europe rate these as their top choice for both racing and adventuring. Their Barracuda model, in particular, has emerged as a perfect boat for adventure racers. Fast, sleek, and roomy (by packraft standards) this tandem boat has risen to the top of the packraft market. For racers looking for the perfect expedition race tandem, MRS offers two versions of the Barracuda – a standard model and one with a spraydeck option. As new partners with MRS, we will be updating this page with a link to an official review of the Barracuda once we are able to launch it for its maiden voyage. By all existing accounts, though, this boat is unrivaled by any other model currently on the market. concluding thoughtsAs always, start where you are. If you only plan to raft once a year, perhaps renting a higher-end boat is a better investment than purchasing a lower-end one. Packrafting Adventures and Back Country Packrafts are both great options for rentals. If you see yourself rafting more regularly, think about your needs, interests, and how much you want to invest. Financial considerations aside, know that packrafting is not quite as straightforward as it seems. It takes time to figure out how to pack efficiently, how to inflate and deflate the boats quickly, how to stow your gear once you hit the water, and how to share a small boat if paddling a tandem. The boat will handle differently, especially in whitewater, from your standard canoe or kayak. Showing up to a race without any experience will likely result in a fair degree of frustration.

Adventure racing legend, friend, and teammate Mark Lattanzi wrote an excellent book on the topic of navigation. Go read it. Rather than do a deep dive on technicalities of navigation, here are some general reflections on big questions and strategies to consider as a navigator and as a team. Expeditions vs. shorter eventsNavigation tends to be “easier” in multi-day races, in that there are fewer CPs and most of them tend to be relatively easy to find. Shorter adventure races typically include a fair bit of micro-nav or even challenging orienteering. You might be looking for a checkpoint every fifteen minutes in a short race. In an expedition race, you might travel for fifteen hours between checkpoints. The challenge often is more in the route finding than the precision, as there are often different options to traverse these long distances. For the Endless Mountains, expect a hybrid approach to race design. Some legs will be relatively straight forward navigationally, with few checkpoints. You will also encounter some navigation that’s more challenging than you would typically find in many expedition races.

|

|

- Make sure you know which maps you need when (as noted in the last Expedition Playbook post, don’t make the classic mistake of storing maps in a bike box only to find you needed them in your paddle bag… we share this from experience…). Remember, the race will start off like any other, but in a few days, things can go sideways fast when it comes to navigation. If your maps are a mess going into the race, it’s going to turn a challenging stage into an absolute mind bender on Day 4.

- Make sure you pay close attention to the instructions and rules. There will be a lot of information to process. Don’t rush it and miss the out-of-bounds trail or road and then get penalized or disqualified for making a mistake during the race. Many navigators (including Rootstockers) make the mistake of succumbing to the pressures that come with pre-race route and map planning. If you need to take some extra time to prep, label, and organize your maps, do it. Ten extra minutes of map prep is worth it if it saves ten hours of mistakes.

|

Autopilots. Especially when building or breaking down bikes, we’re grateful for their simple attachment systems and don’t miss the maddening nuts and bolts many other boards require. It may be fine to mount those boards in your garage for a weekend ride, but no one needs a Mensa puzzle on day five. You just want to build your bike, throw on a map board, and go.

| Beyond this, navigation comes down to experience. The more, the better. Incorporate navigation into your training: go to some orienteering meets, compete in some weekend adventure races, print out a topo map from Caltopo, mark it up, and go practice (if you have a GPS device, you can check out your route either while in the woods or afterwards and see how you did). |

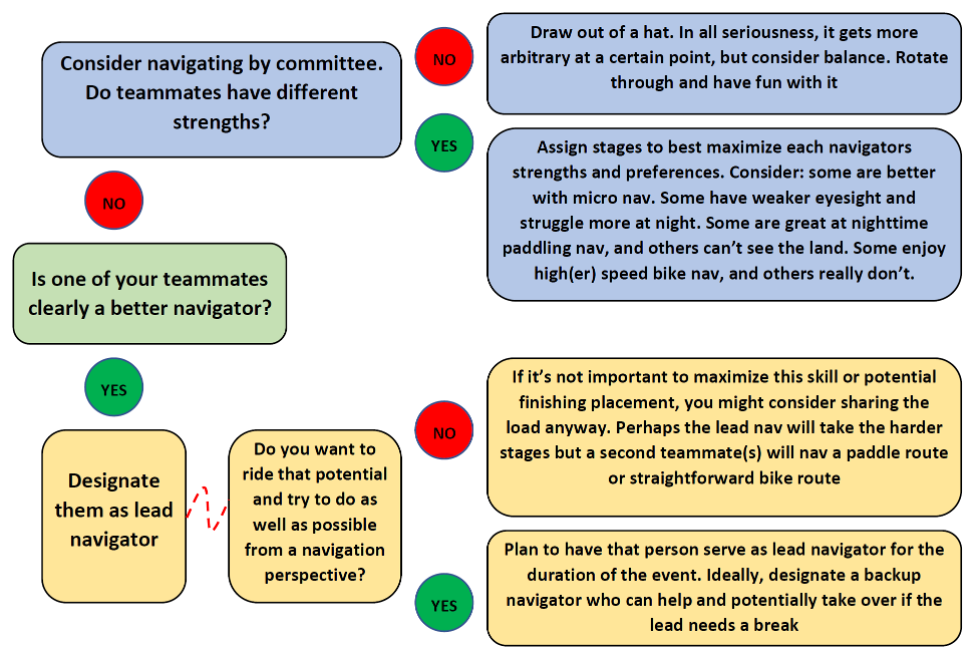

Even better, practice navigating with your team and work on navigating as a unit rather than leaving it all up to one person. Have everyone work on pace-counting and following bearings, so that everyone can be a better, more effective backup navigator. The more navigation becomes a team effort, the more engaged everyone can be, especially when folks start getting tired. This doesn’t mean navigating by consensus – you want to be careful not to create a “too-many-cooks-in-the-kitchen” situation – but some of the best navigators in the sport lean on others to maximize the team’s performance.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed