|

A decade ago, few adventure racers had ever seen a packraft, and many had not even heard about the sport that traces its roots back to Alaskan backcountry exploration and the famous Alaskan Mountain Wilderness Classic. In the ensuing years, the sport has taken off and is now commonplace in many expedition-length events in the US. Even shorter events are beginning to integrate packrafting into their courses. Along the way, there has emerged a cottage industry around the sport, with multiple companies producing great boats to match different price points and many outfitters offering rental service to racers and adventurers alike. Unlike other equipment, investing in a raft can be intimidating: compared to bikes, headlamps, or other standard items found in a gear closet, it can be hard to test out packrafts or even get your hands and eyes on them to assess them before laying down the credit card. In this edition of the Expedition Playbook, we aim to offer guidance on some of the basics, but we will not be dissecting nuances like seats, materials, gear storage, and inflators (manual and electronic; yes, there are electronic inflators teams are using). For more information on some of these details and more (including DIY options), check out this article. And as always, ask around. Many experienced racers have invested in boats at this point, and most have experience with different brands. Online reviews can be helpful, but beware: many packrafters are not racing with their boats, so what might work for the average rafter might not translate well to AR and racing. Before we dive in: one elephant in the room: WHICH raft should we buy? We will save specific recommendations for the end of the article, but here are some considerations worth exploring. costPerhaps the number one question that comes up for the new packrafter is: how much money do I need to invest in this equipment? It’s a fair question, and even cheaper packrafts can carry a degree of sticker shock, as they will still run you at least several hundred dollars. Some considerations:

So… what about the cheaper boats? Are you saying I have to shell out four figures for a boat? Not necessarily. Consider the following, and if you can check off these boxes, then you might be fine with a more affordable option.

Two further considerations as you decide whether and how to invest in rafts. First: many seasoned racers started their packrafting careers in more affordable boats, convincing themselves (and being convinced online) that there isn’t much difference between lower-end and higher-end brands. Often, these racers ended up reinvesting in new rafts within one or two races, after seeing how different they actually perform on the water. If you have plenty of disposable income, maybe this isn’t a big deal, but investing in a $500 boat only to go out and buy an $800-1000+ boat within a year or two is a bummer. Second: Especially in day-long events, you’ll see some teams invest in what literally might be a pool toy. Odds are good that this isn’t what race directors had in mind when they were designing the packraft section of their race. If it happens to be a relatively superficial and short section, you may be able to get away with a $40 beach raft from Amazon, but more likely than not, your experience probably won’t end well. doubles vs singles Another common question that comes up: do we buy a tandem raft or a single

Of course, all races are different, and unless you really are a gear junkie, you probably aren’t going to invest in multiple rafts for different conditions (though many experienced racers do, over the course of several years). Some additional general considerations:

*Expedition Oregon is the clear exception to these norms. The race often includes more technical paddling. It’s safe to assume that teams you should be more prepared for this race than most, and if there is ever a time to consider extra gear like spray decks, it’s here. TrainingIf you have considerable paddling experience, transitioning to a packraft may be relatively straight forward. They will handle differently than kayaks and canoes, but you will likely be able to adjust using your experience quickly enough. Even then, it is valuable to seek out instruction and guidance from experienced packrafters. And if you are jumping into packrafting without much paddling experience, you absolutely should consider some training. In the Northeast, Eric Caravella recently started Packrafting Adventures. Training like this is invaluable, and Eric is offering discounted rates to registrants of a number of adventure races that are including packrafting in 2022, including the Endless Mountains. Reach out to us or to Eric for details. While packrafting is still a fledgling discipline under the American Canoe Association, a growing number of instructors often are able to set up courses for teams or small groups if there are no available classes. the goodsOK. “Just tell me what to buy,” you say. We’ll begin at the beginning: the history of adventure racing, in the USA at least, has long been intertwined with Alpacka Raft. For over a decade Alpacka dominated the packrafting industry. There were a few other companies offering more affordable options that some swore performed nearly as well. They didn’t. In these boats racers often encounted torn-out bottoms, ripped seams, poor tracking, and heavier weights (while still being more damage-prone). In short, no one could hang with Alpacka. In recent years, however, a number of new and exciting options have hit the market, which has opened up all sorts of new, and more complicated, decisions for adventurers. In 2022, you will see a more diverse array of packrafts at any given race, even among the more competitive and experienced teams. For one summary of some of the recognized brands, check out the relevant section in this article. At Rootstock Racing, we are excited about our new partnership with Microrafting USA. MRS packrafts have cemented themselves as a go-to raft on the international racing scene; many elite racers in the South Pacific, Asia, and Europe rate these as their top choice for both racing and adventuring. Their Barracuda model, in particular, has emerged as a perfect boat for adventure racers. Fast, sleek, and roomy (by packraft standards) this tandem boat has risen to the top of the packraft market. For racers looking for the perfect expedition race tandem, MRS offers two versions of the Barracuda – a standard model and one with a spraydeck option. As new partners with MRS, we will be updating this page with a link to an official review of the Barracuda once we are able to launch it for its maiden voyage. By all existing accounts, though, this boat is unrivaled by any other model currently on the market. concluding thoughtsAs always, start where you are. If you only plan to raft once a year, perhaps renting a higher-end boat is a better investment than purchasing a lower-end one. Packrafting Adventures and Back Country Packrafts are both great options for rentals. If you see yourself rafting more regularly, think about your needs, interests, and how much you want to invest. Financial considerations aside, know that packrafting is not quite as straightforward as it seems. It takes time to figure out how to pack efficiently, how to inflate and deflate the boats quickly, how to stow your gear once you hit the water, and how to share a small boat if paddling a tandem. The boat will handle differently, especially in whitewater, from your standard canoe or kayak. Showing up to a race without any experience will likely result in a fair degree of frustration.

1 Comment

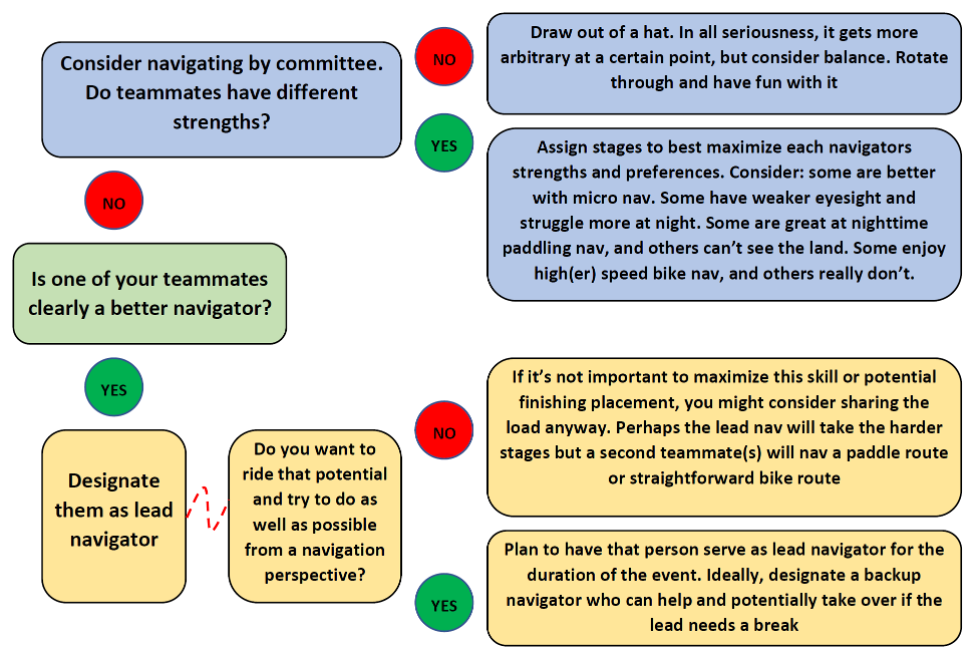

Adventure racing legend, friend, and teammate Mark Lattanzi wrote an excellent book on the topic of navigation. Go read it. Rather than do a deep dive on technicalities of navigation, here are some general reflections on big questions and strategies to consider as a navigator and as a team. Expeditions vs. shorter eventsNavigation tends to be “easier” in multi-day races, in that there are fewer CPs and most of them tend to be relatively easy to find. Shorter adventure races typically include a fair bit of micro-nav or even challenging orienteering. You might be looking for a checkpoint every fifteen minutes in a short race. In an expedition race, you might travel for fifteen hours between checkpoints. The challenge often is more in the route finding than the precision, as there are often different options to traverse these long distances. For the Endless Mountains, expect a hybrid approach to race design. Some legs will be relatively straight forward navigationally, with few checkpoints. You will also encounter some navigation that’s more challenging than you would typically find in many expedition races.

|

|

- Make sure you know which maps you need when (as noted in the last Expedition Playbook post, don’t make the classic mistake of storing maps in a bike box only to find you needed them in your paddle bag… we share this from experience…). Remember, the race will start off like any other, but in a few days, things can go sideways fast when it comes to navigation. If your maps are a mess going into the race, it’s going to turn a challenging stage into an absolute mind bender on Day 4.

- Make sure you pay close attention to the instructions and rules. There will be a lot of information to process. Don’t rush it and miss the out-of-bounds trail or road and then get penalized or disqualified for making a mistake during the race. Many navigators (including Rootstockers) make the mistake of succumbing to the pressures that come with pre-race route and map planning. If you need to take some extra time to prep, label, and organize your maps, do it. Ten extra minutes of map prep is worth it if it saves ten hours of mistakes.

|

Autopilots. Especially when building or breaking down bikes, we’re grateful for their simple attachment systems and don’t miss the maddening nuts and bolts many other boards require. It may be fine to mount those boards in your garage for a weekend ride, but no one needs a Mensa puzzle on day five. You just want to build your bike, throw on a map board, and go.

| Beyond this, navigation comes down to experience. The more, the better. Incorporate navigation into your training: go to some orienteering meets, compete in some weekend adventure races, print out a topo map from Caltopo, mark it up, and go practice (if you have a GPS device, you can check out your route either while in the woods or afterwards and see how you did). |

Even better, practice navigating with your team and work on navigating as a unit rather than leaving it all up to one person. Have everyone work on pace-counting and following bearings, so that everyone can be a better, more effective backup navigator. The more navigation becomes a team effort, the more engaged everyone can be, especially when folks start getting tired. This doesn’t mean navigating by consensus – you want to be careful not to create a “too-many-cooks-in-the-kitchen” situation – but some of the best navigators in the sport lean on others to maximize the team’s performance.

If sleep strategy is the fifth discipline of expedition racing, transitioning is the sixth. For some teams, it may also be the most important. Consider the following:

Let’s say your race has seven transition areas (FYI, many expedition races have several more TAs than that). A savvy, experienced team may be able to average 15-30 minutes in any given TA – let’s call it 20 minutes for the sake of easy math. Some may be even faster, especially early in the race (and excluding sleep strategy). This team will spend 140 minutes in transition over the course of the race.

Now, a less experienced team rolls into their first transition. They are exhausted and hungry. They haven’t fine-tuned their strategy or honed their bike breakdown. It’s not uncommon for a team like this to spend 2 hours or more sorting and swapping out gear, changing shoes, refueling, changing clothes, and repacking. Compound that over seven TAs and that’s 840 minutes – 14 hours of race time, more than half a day. In a race with shorter stages and more TAs, it’s not unheard of for less experienced teams to spend 18-24 hours in transition.

These lost hours can dash podium hopes for pointy-end races. They can derail full-course dreams for mid-pack teams. They can cause teams to miss time cutoffs, and they may be the difference between officially finishing and not.

TAing is a skill that top teams work at tirelessly and endlessly. Adventure racing is all about efficiency, and efficient TAs mean “found” time to spend on the course.

So, how do you get there?

Let’s say your race has seven transition areas (FYI, many expedition races have several more TAs than that). A savvy, experienced team may be able to average 15-30 minutes in any given TA – let’s call it 20 minutes for the sake of easy math. Some may be even faster, especially early in the race (and excluding sleep strategy). This team will spend 140 minutes in transition over the course of the race.

Now, a less experienced team rolls into their first transition. They are exhausted and hungry. They haven’t fine-tuned their strategy or honed their bike breakdown. It’s not uncommon for a team like this to spend 2 hours or more sorting and swapping out gear, changing shoes, refueling, changing clothes, and repacking. Compound that over seven TAs and that’s 840 minutes – 14 hours of race time, more than half a day. In a race with shorter stages and more TAs, it’s not unheard of for less experienced teams to spend 18-24 hours in transition.

These lost hours can dash podium hopes for pointy-end races. They can derail full-course dreams for mid-pack teams. They can cause teams to miss time cutoffs, and they may be the difference between officially finishing and not.

TAing is a skill that top teams work at tirelessly and endlessly. Adventure racing is all about efficiency, and efficient TAs mean “found” time to spend on the course.

So, how do you get there?

Pre-race

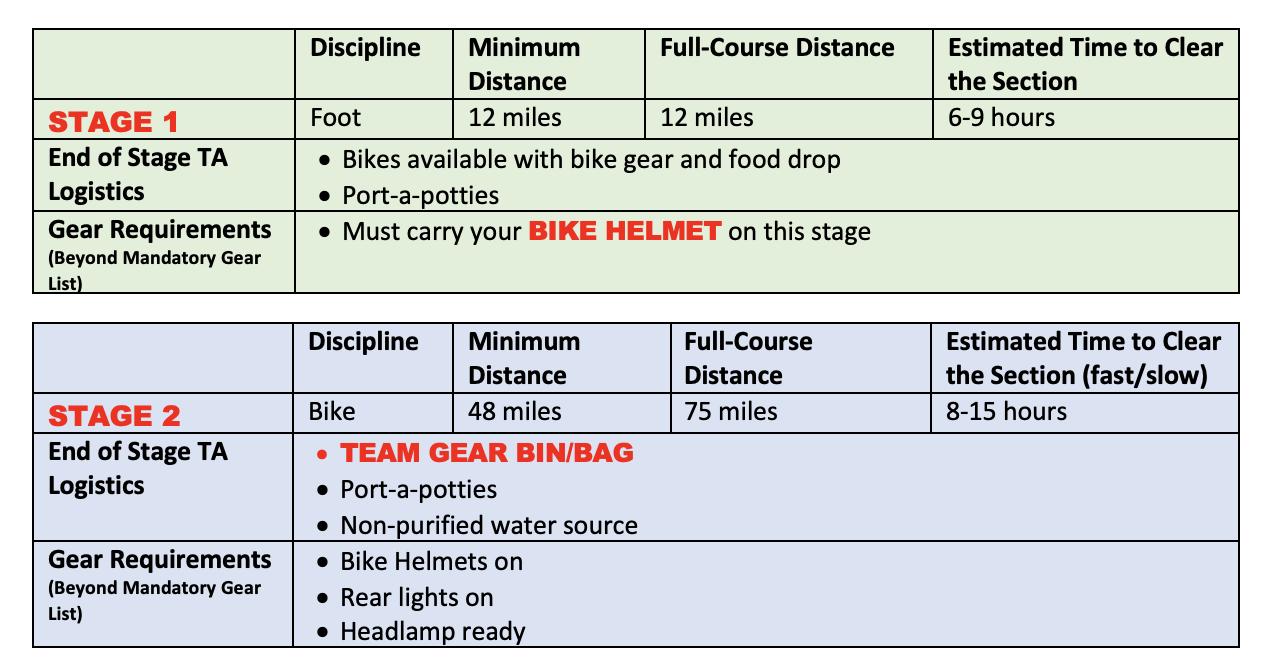

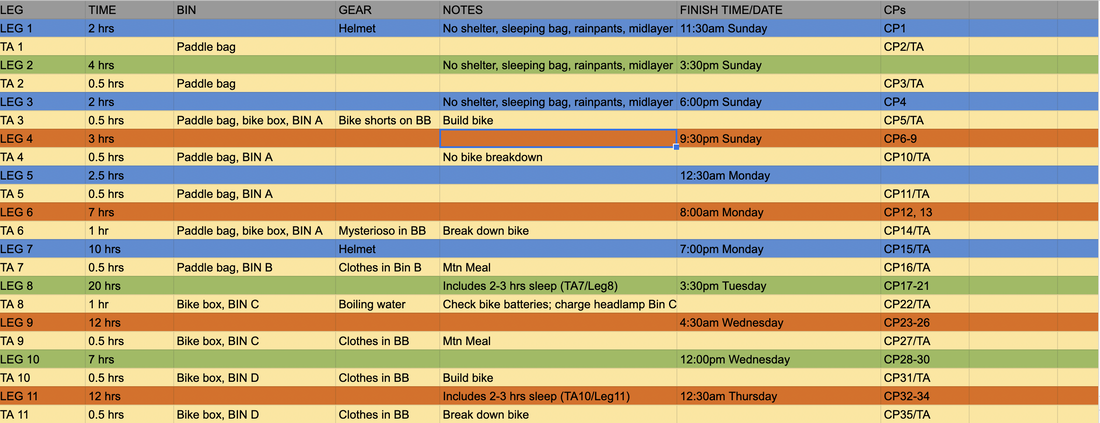

Sometime before race week, you will likely receive a race planner or schematic from the RD. These planners are always a bit different, but at a minimum they tend to provide teams with distance estimates and time estimates for each leg of the race. They will typically offer the order of stages and disciplines, and many will provide specific details that help with planning, strategizing, and packing. Such details may include what amenities are available at specific TAs and what bins, boxes, or bags you will receive.

In a sense, the race has begun once these planners are distributed, and experienced teams will spend hours and hours working individually and as a team to prepare for the race at home: coordinating gear, planning for food and transitions, and organizing TA bags and bins. Obviously, you won’t have all the information you will need, but you can do a considerable amount of prep work, saving you time and energy during registration and in those precious hours on site before the race begins.

This effort can be compounding. The hours spent at home studying that schematic and applying what you can to gear, food, and clothing prep will translate to better preparation, less stress, more sleep, and fewer mistakes at race HQ before the start. You will then have more time and peace to adapt as you learn more of what to expect from the event. And the next thing you know, you are hours and hours ahead of other teams who didn’t do this important work.

When examining pre-race schematics, take note of the following:

This effort can be compounding. The hours spent at home studying that schematic and applying what you can to gear, food, and clothing prep will translate to better preparation, less stress, more sleep, and fewer mistakes at race HQ before the start. You will then have more time and peace to adapt as you learn more of what to expect from the event. And the next thing you know, you are hours and hours ahead of other teams who didn’t do this important work.

When examining pre-race schematics, take note of the following:

- Distance and time estimates. Do they provide full-course options and short-course options? Be aware that one of the most common mistakes newer racers make is overestimating their abilities. You may be well trained, you may have experience in a lot of other sports and outdoor escapades, but nothing is like AR. Very few teams are able to walk into their first race, especially an expedition, and come close to achieving the advertised fast times. All but a few will assuredly end up on some version of a short course. Know that “Fast/Full Course” estimates typically are founded on the following assumptions:

- They are based on the performance of the best teams likely to show up to a race. Typically, at a multi-day race, this means the top teams in the world. These teams are the best for a reason. Recognize that even many podium-contending teams look at those fast times and add a couple hours… or more.

- Fast times assume clean navigation and no issues. They don’t take into account navigation errors, injury, mechanical issues, team dynamics, illness, the time you might spend sleeping, and sleep-deprivation-induced sluggishness.

- They also don’t take into account weather conditions, which can and do blow up time estimates.

- RDs cannot predict how any team’s performance may change over the course of multiple days. It’s hard enough when trying to predict for fresh teams on day one. Most RDs’ fast estimates not only assume a clean performance on a given section and pleasant weather; they also assume fresh bodies and minds.

ACTION ITEM: Talk with your team. What do you think is realistic based on the information you have and your team’s collective abilities? Estimate the time you expect to be on that leg. Pack a food bag and clearly label it for that stage of the race. Set aside any clothes, shoes, or gear you might want for that specific leg.

- Water. What water will be available in a given transition area. Potable water? Natural, untreated water source, hot water?

- Consider whether you will need to find water before entering or after leaving the transition area. Many TAs have water in some capacity, but not all. Don’t assume there will be water to drink or use.

- If water is available, cooking a hot, bag meal is an option. Take note of that and consider it in your planning.

ACTION: Use this information to identify whether you will need to work harder for water. You don’t want to get stuck banking on hydration only to find there is none. You should also use this information to plan for hot meals or drinks that requires water. Pack your stoves, meals, and other gear into the proper bag, bin, or box.

- Food. As is true in adventure racing more generally, you should expect to be self-sufficient and self-sustaining. That said, in expedition races, you may find yourself able to cash in on food that doesn’t require you to pack and plan.

- A TA may be in a town or near a store or restaurant. You may only discover this when you get your maps or during a pre-race briefing, but sometimes RDs will include it on the logistics planner. If you plan to purchase food, make sure to bring some money or credit cards (if you don’t know whether a card will be accepted, it’s a good idea to bring both).

- Occasionally some RDs will provide some food themselves. You may know this ahead of time via the logistics planner, or you may get a surprise when you roll into TA.

- Alternatively, RDs may include the local community when it comes to offering food. Food trucks and highlighted eating establishments or shops are often included in the event. RDs may coordinate with such vendors to stay open at odd hours or set up at a TA. Often, racers pay out of pocket, but such offerings are often delightfully convenient and well-timed.

ACTION ITEM: If the RD is offering food themselves or arranging it for purchase, plan to take advantage of it. Race food, no matter how thoughtful and tasty, tends to get old long before you reach the finish line, and taking advantage of provided calories or food and drink for purchase is well worth the money. Make sure you have sufficient cash and credit cards safely packed for the race. And know when those calories will be available to minimize overpacking food you won’t need (or want).

- Electricity. This is not common, and most racers don’t even consider it, but take note of it if it’s mentioned in the logistics planner. This may come in handy with charging lights and batteries. Most racers make sure they have ample battery time in their arsenal to avoid needing electricity, but some like to pack chargers in case.

- Bins, Bags, and Boxes. The logistics planner will likely tell you what you will see in each transition area. You may see all of your gear in every transition, but most likely you won’t. It becomes crucial to study the schematic and figure out what bins you will see where, what TAs will have your bike boxes, and when will you see your paddle bags.

- Some races allow each racer a personal bin. Some require all members of a team to use a single bin for a given transition. In both situations, it can get confusing fast, so make sure you really study the schematic closely and have bins clearly labeled and organized.

- Determine what food bags should be in which TA vessel.

- Determine where to store extra clothes and shoes.

- Consider where you might plan to sleep. Make sure sleeping gear (if you aren’t going to be carrying it) is earmarked for the proper location.

- Extra gear? Sunscreen? Foot care? Trekking poles? It’s a good idea to spread such gear around to make sure that it’s not only available when you plan to use it but also when you might not.

- Extra food? Most racers pack too much, but if you have extra space and weight, figure out where best to store it all.

- Keep thse weight restrictions in mind, especially if teammates have to share bins.

ACTION ITEM: Build a spreadsheet or some sort of organizational aid to help. It all starts with these bags and bins. Knowing exactly where you will see them and roughly when will then inform the rest of your pre-race packing. Making food bags, clearly labeling them, storing them, etc. Talk as a team. This may be one of the most important things you do before racing, getting to know each other aside. Triple check all of it.

| A final note on pre-race preparation. There is a tendency overthink and over-organize for TAs. One might think that the more nuanced your organization plans, the better. The reality is that TA bins tend to blow up very spectacularly very quickly. You will end up changing your mind on what clothes to bring for a given stage, mixing up your food, adapting to stages that are either longer or shorter than expected, and depositing wet clothes and gear in your bin. This is a |

good opportunity to practice that old adage, KISS: Keep It Simple, Stupid.

Big zip-locks are your friend. Being able to see what’s in your bags can increase efficiency and reduce the need to use precious mental energy, sorting through which bags to grab on Day 4.

Big zip-locks are your friend. Being able to see what’s in your bags can increase efficiency and reduce the need to use precious mental energy, sorting through which bags to grab on Day 4.

Now you are racing...

If you have done well planning, organizing, and packing your bins and bags, the real key to race-week execution is in communication with your teammates. Use the last thirty minutes of each leg to talk about the upcoming TA. What stage are you going to embark on? What gear will you need? What food needs resupplying?

As you come into TA, you should consider the following tasks, depending on what the next stage might be.

As you come into TA, you should consider the following tasks, depending on what the next stage might be.

- Signing In and Out? Do you need to check in? Do you need to punch a physical flag? Make one team member responsible for this job – both as you enter the TA and as you depart.

- Bikes. Are you breaking down bikes? Building bikes? Loading bikes on a truck? What gear can your leave with your bikes? Any repairs you need to address? Lights on? Lights off?

- Paddling. Assemble paddles, make sure you have the proper safety gear, etc. If you have to portage, how are you setting up for that? Which teammates are paddling together?

- Gear. Are there any unique gear requirements? Perhaps you need to bring sleeping gear. Maybe you need climbing helmets and harnesses or you want your poles for a long trek.

- Body Maintenance. Any hot spots, blisters, or other issues that need basic attention? Any more significant injuries that you should run by a medic if one is available). Re-apply lube, take care of bad chafing, apply sunscreen, do a tick check, rewrap a turned ankle, etc.

- Shoes and Clothes. Is this an opportunity for fresh clothes and shoes? If you’re soaking wet and the sun is out, take advantage of this to help reduce chafing and infection. That said, if it’s pouring, maybe a full change of clothes isn’t worth it. Do you need to carry extra shoes with you for an embedded foot section? Should you bring a puffball or extra warm gear on the next stage?

- Food. Resupply food. Drop your trash from the last stage if you’re able. Do you have the time and resources for hot meals? Should someone go check out that local pizza shop next to the TA and place an order while everyone else works on bikes?

- Maps. If you have stored maps in TA bins or bikes boxes and need to swap, do so. Be careful though: while it’s a great idea to break maps up and minimize weight (a full set of expedition race maps can add pounds to your pack), many teams, including the best in the world, have made the mistake of mixing up maps. It’s demoralizing to realize that the maps you packed in your bike box are, in fact, for a paddling stage later in the race.

- Sleep. As discussed in our sleep article, consider whether bedding down in the TA is the best option for you team. If it is, have a plan. Ideally, everyone can attend to their business, prep what they need for the next stage, eat, drink, take care of their feet, and then crawl into a sleeping bag for some quality or emergency sleep. If someone is in bad shape, that may not be reasonable. Consider sending them to sleep immediately (ideally with some food in their bellies!) and have the other teammates complete the TA chores. Make sure those staying up longer have ample time to sleep as well; don’t shortchange them.

- Stay Positive. Know that the single hardest part of expedition racing is keeping everyone going mentally. When you stop – whether it is to sleep, take a break, eat, attend to an illness, or simply TA – it’s not uncommon for someone on the team to confront the AR demons, taunting them to drop out. When you are in TA, it’s much easier to entertain dropping out. On our team, more often than not, the tears, the deepest doubts, and the hardest questions come out in TA rather than out in the woods or on the trail; there is a release that comes when you crawl into TA after a particularly hard stage or experience. Support each other, stay focused, and get back out there. Getting on your way usually helps the storm clouds pass.

| For the most part, this covers it. That said, TAs are some of the most interesting places on the race course. Adventure racers are a creative lot, and it’s fascinating to see the extra items, big and small, that emerge out of TA bins. The tricks of the trade, the unique food options, the hints of home and luxuries – we could likely write an entire article series out of a single TA. Prioritize your race gear, food, and clothes first, but then include what you want: toothbrushes, mouth wash, coffee maker, pillow, towels, a can of artichokes, a letter or photo from home, whatever you will need to get you moving when things are hard and keep you moving when the energy is up. |

Finally, as much as we privilege efficiency, there are times when TAs should serve as a legitimate break. Sometimes, you need to slow things down and do some quality work preserving a teammate’s mental or physical health to be able to continue. This is the razor edge of adventure racing: balancing the desire to maximize every minute and keep things moving and the need – sometimes – to slow it down or even stop, knowing that a couple extra hours of preservation might translate to hours gained later on the course or a more realistic chance to finish, or even win, the race.

Finally, as much as we privilege efficiency, there are times when TAs should serve as a legitimate break. Sometimes, you need to slow things down and do some quality work preserving a teammate’s mental or physical health to be able to continue. This is the razor edge of adventure racing: balancing the desire to maximize every minute and keep things moving and the need – sometimes – to slow it down or even stop, knowing that a couple extra hours of preservation might translate to hours gained later on the course or a more realistic chance to finish, or even win, the race.

Let’s face it: adventure racing does not make for pretty feet. Even in day-long races, you’re spending significant time on your feet, and even when you aren’t, you’re likely feeling the effects of the grime and wet you’ve subjected them to. In a multi-day race, the soreness, the blisters, and the abrasions will be compounded.

So, what can you do about it?

(Note: we're going to refrain from photos in this one!)

So, what can you do about it?

(Note: we're going to refrain from photos in this one!)

pre-race

First, spend time on your feet. This means more than just getting out for long runs. Hit the trails with a pack. Add some weight. Mimic the gear, food, and water you will haul during the race and toughen those feet up.

Second, do a little bit of learning. Read, watch videos, and familiarize yourself with first aid items and strategies to treat blisters, manage infections, and bandage wounds. It’s not a bad idea to practice blister bandaging and experimenting with dressings to see what works and what actually stays on when you get out in the woods. Youtube is a great place to learn different techniques.

Gear up

Experienced adventure racers rely on a few crucial items aimed at taking care of their feet during the race.

- Shoes. This should go without saying, but find shoes that work for you.

- You will want shoes that are reasonably light but sturdy enough to hold up under unforgiving conditions. Few shoes are designed with the wet, dirty, off-trail conditions of an expedition race in mind. Do your homework. Ask around. See what works for others and then try them yourself – before your race.

- Be aware the ultralight shoes that may get shredded when you’re bushwhacking off trail.

- Consider a shoe with a protective toebox.

- The most important thing you can do is to make sure that you find the right shoe for your feet and then test them out with some long sessions and see how your body responds. Some racers prefer the ultra-padded soles of Hokas, while others are more comfortable in the ultra-stable Salomons. Some like a shoe that hugs their feet; others want a wide toebox so that they can move around. There is no one right shoe, but there is likely a right shoe for you.

- Buy big. If you are new to ultra-endurance events, be prepared that your feet will likely swell. The shoe that is comfortable but snug on Day 1 may be so tight that it causes painful blisters on Day 4. Many adventure racers buy a half size up, or even a full size. You may also consider bringing a bigger pair for the second half of the race.

- On that note, bring extras. As we discussed in our Expedition Playbook entry on gear, if you are able to pack extra shoes, do so. Being able to mix things up helps your feet. New or fresh shoes may relieve rubbing and will give your feet a break from day-old grit and grime.

- You will want shoes that are reasonably light but sturdy enough to hold up under unforgiving conditions. Few shoes are designed with the wet, dirty, off-trail conditions of an expedition race in mind. Do your homework. Ask around. See what works for others and then try them yourself – before your race.

- Lubricant. There are a number of excellent lubricants out there that all will help keep your skin healthier during the race. Find lube that holds up well in wet conditions and ideally provides lasting protection. Some lubes offer antibacterial protection. Some are designed with more natural ingredients. Some will last longer. Some may stain your clothing. Once again, experiment. Try it on a long hike; try it in wet conditions. Train with it and see how your feet feel and respond in gnarly conditions.

- Insoles. Consider inserts if your feet need some extra support. You might consult with a podiatrist for specific recommendations here.

- Trekking Poles. While they may not immediately relate to your feet, using trekking poles can relieve your feet of some of the inevitable pounding and wear and tear. This might translate to more efficient travel later in the race and might make the difference between a team being able to shuffle and jog versus hobbling along.

- Socks. Here again, personal preference is key. Some folks like thicker and more cushioned socks. Others prefer something thinner. Experiment. You may get by with a certain sock in shorter events or in training. But what happens when you spend 10-20 hours on your feet… or longer?

race week

Pro-Tip: if you have found your preferred lube (at Rootstock, we are big fans of Foot Kinetics’ Hike and Run Goo for our feet), lube those feet up for several nights in advance of the race, throw on a pair of socks, and go to sleep. This “prepping” can pay dividends during the race by developing a level of protection before you head into the woods

Before the race begins, make sure you store lube for all stages of the event. It’s a good idea to keep bigger tubes in bins, bags, and boxes that will be available in transition areas. You will also want to make sure at least one member of the team is carrying lube on the course in case (when) you need to stop to address foot issues.

Once out on the course:

- Listen to your body. Your feet will be sore, no question. Tylenol, shifting weight around the team, and avoiding pavement may provide some relief. Make sure that you’re tuned into what you’re feeling and take proactive measures to address it before it moves from inconvenient to emergent.

- To that end, identify hot spots as early as possible. The classic mistake that so many people make is to gut it out. Sure, if you are a mile away from the end of the final foot section, put your head down and get to the finish line. Otherwise, stop and address the issue. A few minutes to clean feet, change socks, reapply lube, or manage an oncoming blister is absolutely worth it. If you’re stubborn (and we’ve all been there), you may throw away hours of time later in the race when your feet are too ravaged to move efficiently. That isn’t a nav mistake or a bonk that you can recover from; badly blistered feet won’t heal during the race, and even the toughest competitors may succumb to bad feet if the blisters are bad enough or infected.

- Be prepared to treat blisters or wounds. Make sure you have a small foot-care kit, and know how to use it. Here are some crucial items to have at your disposal, though there are various different approaches to blister management.

- Needle/safety pin. You may need to drain a blister; make sure to sterilize your needle first. Draining the blister in a controlled environment can prevent it from tearing or ripping on its own, a situation that can make you more susceptible to infection or create significant pain. Pop the blister with a sterilized needle early if that hot spot starts to bubble and gently drain it of fluids. It can help to poke two holes in the blister to facilitate drainage.

- Clean the wound. If you have some fresh water, rinse off your feet. Then use antiseptic wipes (go for iodine wipes; alcohol wipes will work, but they have been shown to kill tissue).

- Then you will want to apply some antibiotic ointment. This is crucial to help prevent an infection that might set in before you reach the finish line and can clear your feet properly.

- Covering the blister site can be tricky. Some people use moleskin. Others prefer dressings specifically designed for blisters. Sturdy band-aids also work. The key is something that will stay secure and protect the site. Again, make sure there is ointment in there. Not only will this fight infection, but it adds a nice layer of lubricant to prevent further rubbing. You may want to consider using some athletic tape or wrap to more fully secure the dressing.

- Finally, apply Tincture of Benzoin. Tincture can help secure a bandage to your skin and is valuable in helping with blister dressings.

If sleep strategy is the hidden discipline of expedition races, your feet are your silent teammates. You need to train them, prepare them, respect them, pay attention to them, and nourish them during the race. Just as a teammate driven too hard likely will fold and drop from the race, untended feet are likely to fail you and your team. No one wants to stop mid-race to tend to a hot spot or work on a blister, but taking the time to do it right, like anything else in AR, will pay dividends later in getting you to the finish line

RSS Feed

RSS Feed