|

Up until this point, this Expedition Playbook series has focused largely on training and preparation. Today, we’re going to pivot to in-race considerations. The next several articles will tackle selected topics related to the actual experience, strategy, skills, and approaches that will come up after you and your team cross the start line. First up: Sleep Strategy. Multiple nights of continuous racing is, perhaps, the single biggest difference between shorter day-long events and expedition racing. The sleep deprivation piles up, and past three days, racing straight through really isn’t an option. Even in a 72-hour event, most teams will sleep a bit. Past three days, however, sleep strategy really becomes its own discipline. And it’s an important one. How your team approaches sleep can radically impact your experience and race. Extreme sleep deprivation also adds risk to the event, so safety comes into play. Sleepy racers have a harder time navigating effectively. Exhaustion can breed a false sense of reality, and teams can throw away tens of hours of productive racing to inefficiency, wasted time, mistakes, and more. Tempers fray and sometimes break, and for some teams, bad sleep strategy can become an insurmountable obstacle, preventing individuals or teams from reaching the finish line. At the same time, expedition races are massive undertakings, so there is a constant sense of pressure to GO, GO, GO! Many believe that stopping to sleep means they will run out of time. Those looking to compete against other teams – versus the course – worry that they will fall too far behind. While some of this may, at times, be true, there are a number of myths out there about sleeping…or not sleeping…in an expedition race that deserve your team’s attention prior to confronting sleepmonsters on a dark, rainy night. And with some exceptions, effective and well-timed sleep management will most likely lead to a more enjoyable and successful experience and often times a better finish. Myth #1: Adventure racers don't sleepWe do actually, and many of us try to sleep very deliberately! In races under 48 hours, most experienced racers try to go wire to wire without any shuteye; if you want to compete, you likely won’t be able to afford much if any sleep. Past that 48-hour range, however, most teams start to work sleep into their race strategy. For a three-day race, that may just be a few hours on night two. In races of four days are more, most of the top teams in the world are sleeping two, three, even four hours almost every night once they hit night two. This may not sound like a lot for a sport that runs continuously over several days, but compared to many teams who measure successful sleep in minutes vs. hours, that’s a full night sleep! myth #2: sleeping on the trail is the only way to goYears ago, in the midst of a five-day race (location and teammates shall remain anonymous), we were digging into night two. The team was exhausted, a cold rain was falling, and we were setting off on a leg that we knew would offer us no reprieve. It was the kind of situation that any experienced team knows can end in disaster.

In that unnamed five-day race, another teammate scoffed. “We aren’t out here to sleep in a hotel,” they said. We then “slept” on a cold concrete bus platform two blocks away, shivering for an hour or two… We know adventure racers enter the woods to test themselves against the elements. We also know that a long, cold, dark bike stage will always be more enjoyable if it follows a couple hours of sleeping in a comfortable and warm spot.

Time and again, the more rested teams take advantage of the rest of the field’s fatigued states as multi-day races wear on. Where you sleep really can make a huge difference. Some other considerations on this point:

myth #3: 15 minutes, when someone needs it, is enoughThere are times when a quick nap IS enough, but anyone who has studied sleep or who has experienced sleep deprivation knows that fifteen minutes here and there might be enough to keep the train inching along, but it’s almost never enough to get that train cruising for a sustained period of time. It’s appropriate when you just need to get to the end of the leg and the wheels are coming off, but it should not replace more legitimate sleep. Let’s take the legendary Kiwis from Avaya/Seagate as an example. They tend to race through night one, but they then settle into banking sleep most nights, if not every night, thereafter. Often a couple or even several hours of sleep at a time. Their race resume speaks for itself.

myth #4: ta's are the best place to sleepSometimes they are! But often they are not. True, you may have the luxury of better access to sleeping gear (tents and sleeping bags if you don’t have to carry them on course, inflatable sleeping pads, inflatable pillows, etc.) and you will be near your gear bins, so extra food and clothes will be available.

Sleeping out of TA comes with different challenges (mostly related to what gear you have with you to sleep comfortably and where you will decide to physically lie down), but most experienced teams avoid TAs if there are other options. For other options, review Myth 2! final thoughtsLike anything with AR, there is no right way to approach sleep strategy. The reality is, your team will experience highs and lows with sleep, regardless of how well you plan it out ahead of time. One teammate will be asleep on their feet and the others will be wired. Two people will bank some good sleep on night two, but the rest of the team will toss and turn and “wake up” more tired than when they laid down. You will make a bad decision or be forced into an unplanned sleep that isn’t restorative or productive. You will need to be flexible and adapt, knowing that the best laid plans may be immediately ruined by a navigation error that delays you by several hours, disrupting your entire plan for multiple nights of sleep. Still, planning and strategy can go a long way. Talk as a team and approach sleep as the fifth discipline of expedition racing after running, biking, paddling, and navigation. We’ll leave you with some final nuts and bolts to toss around as you plan for this added challenge:

pace. Take care of your teammates; if this means sleeping, whether it be a maintenance nap or a strategic big block of rest, do it.

You enter the woods for the love of the journey, in all its highs and lows. It’s much easier to enjoy that journey when you are in a good mood, sharper with your navigation, and moving efficiently. Without sleep, it’s much harder to really enjoy life. Race or not.

0 Comments

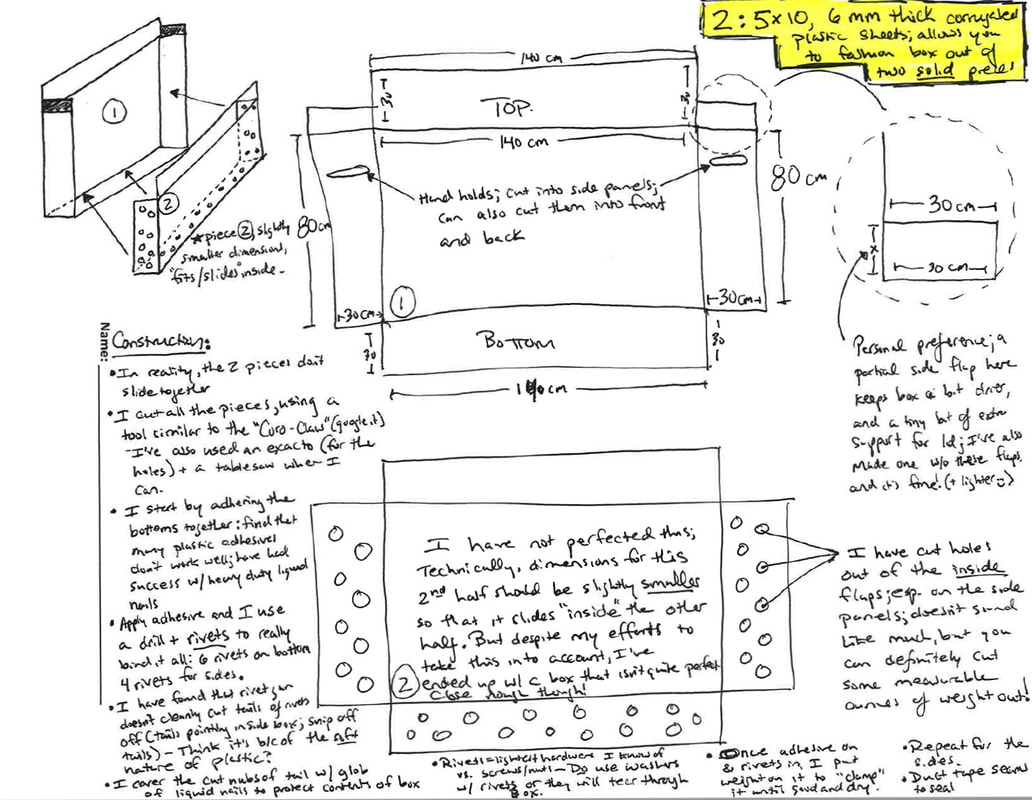

For new expedition racers, bike boxes can freeze you in your tracks, especially if the race you're eyeing requires standard dimensions from the Adventure Racing World Series. Unfortunately, you can’t walk into a local bike shop and buy one, and this is one thing Amazon likely won’t stock…we don't think …actually, it looks like they sometimes do, but as of this writing, they aren't available...we digress... Walk around a transition area or peek into the back of the RDs' U-Haul at most expedition races and you will find a real hodgepodge of bike boxes. Most notably, you will see that many, perhaps most, are, in fact, hand made. So, where does one begin?! Pre-Made Boxes At one time, Crateworks fabricated a bike box that met ARWS dimensions. As of now, they seem to have stopped production on those boxes. Those boxes were not cheap, and they typically didn't seem to hold up as well as some of the better built DIY boxes -- not because the quality of the boxes was poor, but because their ability to break down meant that there were more moving parts, which caused more wear over time than with some firmer less flexible boxes. Still, you didn’t have to put time and labor into building the box yourself, and they were designed to break down, fold flat, and store easily. If you don’t mind spending a bit more, then an option like this is an easy solution. The team from Rogue Adventures in Australia offers a list, which they update periodically, of outfitters currently producing bike boxes. Keep in mind you likely will pay for the box and shipping. The DIY Box OK, so you are going to go it yourself. Here’s what you need to know: DIMENSIONS. As noted above, plan to build your bike box to ARWS dimensions: 140cm X 80cm X 30cm. All ARWS events will use these standard dimensions. If you err on one side of the measurement, go small. MATERIALS. You are looking for corrugated sheets of plastic. Some call this coroplast, others corflute. You can typically buy this in 5mm or 6mm sheets. We have used 6mm for our boxes, with good results. They are a bit sturdier, stand up better when traveling, protect your equipment to a higher degree, and have a long shelf life. We built ours eight years ago, and we haven’t had to do any repair work. Getting your hands on such sheets is the real trick as they can be hard to find. We have had luck at a local sign shop like this, which has stocked sheets of coroplast or has been able to order them, and we have ordered two 5x10-foot sheets per box. You will also need a heavy-duty bonding agent that will work on plastic surfaces, and you will need something to secure sheets together. We have used rivets and washers, which have worked well for us. They don’t weigh as much as other hardware, and with proper washers, they have held up without needing to be replaced. That said, you will need to invest in a rivet gun. We know other racers have had success with their own fastening systems. Ask around. You will need some basic tools: X-acto knife, a tool designed specifically for cutting coroplast (you can live without it, but it makes some of the cutting much easier and cleaner), a drill, a rivet gun (if using rivets), or other tools if using a different fastening system. Finally: when cutting the plastic sheets, consider the surface you are cutting on. Make sure it is a surface that can be marred by the X-acto blade, or use some cardboard to protect the floor. You will also need some heavy weight to help allow the adhesive to set. Finally, make sure you have plenty of time. You will likely need a fair bit of it to complete the project, including multiple time blocks to apply the adhesive and let it dry. Don't wait until race week! Design

Before reinventing the wheel, the previously mentioned article by Rogue Adventure presents a great design with terrific instructions and is worth consideration. Some racers have made clamshell style boxes. These boxes take more effort to design and build, but they open up nicely, and such boxes allow easier access to whatever is packed in the box. Ease of access can really make life seem so much easier on day four of an expedition race! Our preferred model, however, is a simple variation of Rogue’s box. Check out the more detailed “blueprint” above for details. We prefer it for a few reasons:

None of this is to say these boxes are perfect or that you shouldn’t consider alternatives, but we like simple! As always, network: ask other racers what they use, what they have built, and why. What has worked well, what hasn't? Check out some different styles. Mix and match what works for you and what you like from various approaches. In the end, you probably won’t save much in building it on your own, so consider whether it’s worth the time and effort. Just make sure you invest your money and/or time in something that seems durable. The worst is acquiring or building a flimsy bike box that either breaks down during the race or needs to be replaced or rebuilt a year or two later, and even worse than that is the weak box that doesn't do it's primary job: protecting your bike from damage during transportation. The age-old adage of expedition racing is that the hardest part is getting to the start line. For many, the puzzle of packing gear, shipping or transporting it, and transporting yourself is the least enjoyable part of the experience, even if it’s not TRULY the hardest! But don’t let this logistical hurdle stop you; good planning and attention to detail goes a long way to helping minimize that stress. With almost no exceptions, you will fall into one of two categories: you will drive to the race, or you will have to fly. Driving On one level, drivers have it easy. No flights to contend with, no mathematical conundrums as you sort out weight and bag limits for bike boxes and gear bins, no questions of whether to fly with a gear bin or acquire one on site. And it’s a lot cheaper! On the other hand, for a race like the Endless Mountains that requires racers to use ARWS standard bike boxes, it can get tricky figuring out how to transport the bike box to the race. For better and worse, there isn’t too much to say on this front. It’s really about the bike boxes, assuming the rest of your gear will fit in the car. Some have bike boxes that fold up and might be able to lay flat in the car. Easy. For those with rigid boxes, here are your options:

FLYINGFor those flying in from further afield, you have harder logistics. Notes about bike boxes above still apply: how are you going to get all your gear and bike boxes to the airport? How to deal with weight restrictions? How to pack everything without paying the airline a small fortune in extra fees? Here are some tips to consider when flying to you race:

2)Make sure you know what you are allowed to bring on the plane. How many checked bags are you allotted? Carry-ons? How much does each bag cost? Weight restrictions? Size limits? If you have disposable funds, this isn’t as stressful, but if you have a tighter budget, micromanaging each pound becomes important. Know what you are allotted. 1)What is your airline’s policy on bikes? Some airlines have started to allow for the free transportation of bikes, but make sure you know the associated costs, weight, and size restrictions you are dealing with. And read the fine print. Not all routes are treated the same. 2)Airport to race HQ: this often is the hardest puzzle to fit together. Flying and transporting gear is tedious, but you will either figure out what to leave at home for financial reasons or you will shell out for that extra bag. When you land, how do you – and your gear – get to race HQ? Start off by studying the race website. Some RDs include pre- and post-race transportation in the race fee. Others include it as an add-on. Some don’t offer any assistance at all. If the website isn’t clear, reach out to the RD. Some of the best races we have done offered no transportation perks, so don’t let that deter you. That said, make sure you are planning WELL ahead of time to avoid paying extra or ending up stuck without any apparent options to get to and from the race. 3)If your race does not include transportation assistance, consider the following:

packingOkay, you have sorted your logistics, you’ve done the training, you’ve spent your holiday money on new gear, and now you need to pack. On one level, this is straight forward: lay out your gear, organize it, check it two or three or seven times, and then throw it all in some bags and boxes and do it all over again when you get to your pre-race lodging. If you can drive to the race, you are fortunate in that you don’t need to worry too much about overpacking. That said, we like to think of packing as the first stage of the race. This is your first chance to really start thinking about what you are going to need. How you are going to pack your actual race pack? How will your your team distribute mandatory gear? What goes in your bike box? A gear bin? What stays in your pack? How many pairs of shoes do you REALLY need, and is it worth using leftover weight for clothes, food, or something else? Experienced teams show up to the race with a much better handle on their gear. Their food is often already organized into twelve-hour bags, or something that works for them individually. Clothes are packed and organized. Typically, you will receive some sort of race planner from the RD a week or so out, and the savvy racer will figure out how much food, clothing, and other gear will be required on each stage. They will organize that gear at home, label bags for each stage, and save themselves hours of time at the race site before the race starts. This translates to more sleep and less stress. If you are flying, you will have to contend with weight restrictions unless you fork out for extra baggage. Assuming you don’t do that, consider the following tips for packing your gear to fly:

One final tip, from brent...Who is the nicest, friendliest person on your team? I have a theory that if a team travels together and allows that person to lead the way in check in, your chances of saving some money with your bikes and bags go way up. For us, it’s Abby: granted, Abby and I always travel together when we’re both racing (and we are married), so it’s easier for one of us to check the other one in. But time and again, I shut my mouth and hang back. She talks to the desk agents about the race, the bikes, how exciting it is. And we often pay less than we expected. Sometimes they waive the bike fee. Sometimes they charge less for one of the bags or the bike. It doesn’t work every time, but usually we get a great deal! Ask any experienced adventure racer, especially those who have experience in multi-day racing, and you will find that few people went into their first race with all the “best” gear. It’s just too much of an investment. Racers build their gear closet over time, investing in a new major item or two each year. Unless you have the disposable cash to buy every ideal piece of equipment at once, figure out what you really need and know that there are plenty of options to get by. There is also a difference between the best piece of gear and the piece of gear that is best for adventure racing. That ultra-light $400 rain jacket? It will likely get shredded before you come out of the woods on your first monster overland trek. Keep in mind that while online reviews are useful, most reviewers are not putting gear through the ringer the way expedition racers are. Your best bet is to do your research and pricing, and ask some experienced racers for their thoughts, too. To begin, check out the article on gear in USARA’s “New to AR” Series. This piece explores the basics of a standard AR gear list. While it wasn’t written with expedition racing in mind, it is a good foundation for many of the basic gear requirements you will have for an expedition race. Beyond that, here are some additional equipment considerations geared (see what we did there?) specifically toward expedition racing. Note that this post is a little bit more scattershot than some of our others. Gear is a big and unwieldy topic; we've organized it as best we can! ClothingCome to the race prepared for anything. A five-day race means the potential for diverse weather. While the PA mountains are not the Rockies, you may still experience wild swings in temperatures at the Endless Mountains Adventure Race. Late June in Pennsylvania can mean anything from cold rain to sweltering heat and humidity – often within a 24-hour period! Weather forecasts will help, but it’s wise to have options as things can shift during race week. You’ll want to figure out what clothes you’re starting in and then what you’ll need for each subsequent leg of the race, and then you will want to pack strategically, based on the course schematic you will likely receive in the week or two preceding the event. Most racers store dry clothes in as many resupply bags, bins, or boxes as they can. It should go without saying, but leave the cotton at home. Synthetic will dry faster, keep you warmer, and keep you cooler. When planning for cold weather, consider investing in merino wool. It’s a game-changer in regard to performance, and by all accounts it resists the stink that comes from five days of racing like nothing else. shoes

Changing shoes can also help reduce the chances of blisters…or at least blisters that threaten your race. You may not be able to stage a fresh pair of shoes for every section of the race (though some people try to), and you may need to jettison a pair or two to keep your box or bin at weight, but try to bring at least an extra pair or two if possible. Ta gearWhen you’re planning your clothing, take TAs into account, especially the ones where you may end up sleeping. At a minimum, most experienced racers pack lightweight TA shoes. Crocs are popular: they are easy-on, easy-off, and they are airy, allowing your feet to dry out and recover a bit. Likewise, some people like to have an extra fleece or jacket, just for transitions. The longer the race, the harder it will be for your body to regulate temperature. rain gearSome racers invest hundreds and hundreds of dollars into an AR shell. Perhaps in a race with legitimate mountaineering or particularly cold temperatures it is worth it, but more often than not, a solid mid-range jacket will do. Keep in mind: an expedition race is relentless on gear. In an environment like you will encounter at the Endless Mountains, you will be off trail a fair bit - with underbrush poking, ripping, and grabbing at you and your gear. Consider how you will feel if that $500 jacket is damaged or lost during the event.

Regarding rain pants: these are, in some ways, one of your most important pieces of gear. Not only do they help keep you drier and warmer, but they add a nice layer of extra protection when bushwhacking. In woods like those in the PA Wilds, it’s not uncommon to become saturated quickly when you’re bushwhacking. Even if the sun is out, overnight dew and rain can leave woods dripping with condensation and rainwater for hours. If it happens to be cooler, before you know it you will be soaked through and freezing. Rain pants can make all the difference in the world. Here, too, you may not remain entirely dry, but you will stay warm enough to keep racing comfortably. Finally, we recommend avoiding minimalist rain gear, especially for an event like the Endless Mountains. It may save you a few ounces, but it likely will cost you a fair bit of money, and it will almost definitely get shredded right out of the TA. big-ticket itemsSo, what gear should you strongly consider investing more money in? Here are some ideas, though remember, most people don’t drop their credit card on all these things at once. Consider what you want to prioritize and build your collection. Lighting. The cheaper option here is to use lights that run on disposable batteries. These light systems tend to be less expensive, and you don’t have to invest in extra batteries or come up with creative ways to recharge. Most experienced racers invest in higher end set-ups, however. There are several great lighting companies including Lupine Lighting, Dinotte, Light in Motion, and more. These systems produce more light output, and many, like Lupine can now be programmed to put out different lumens based on personal preference and comfort. Some racers race with one light throughout the race. Others have a different setup for bike sections. You want to consider battery run-time, weight, and lumens/light output when determining how to invest. The Rootstock Race team has been supported by and races with Lupine Lighting, and we have been thrilled with the power, battery life, ease of use, and service options that come with the investment. We can't recommend them enough! Paddles. Most seasoned racers are racing with two or four-piece carbon kayak paddles. Such a paddle can cost several hundred dollars, but they are much lighter and can break down for transport in your pack, which comes in handy if you have to carry paddles overland for a stretch. They are lightweight, which also means less wear and tear on your body. Multi-piece paddles also pack easier in paddle bags, and they take up less of your weight allotment. Packs. Really, any pack will do, but you want something durable, functional, and comfortable. You will be wearing your pack(s) for several days, so make sure you have something that fits your body well, or be prepared for some serious chafing. Consider how you will pack your gear, what you want to access quickly, etc. Many racers love packs with endless side pockets for small items and food; others find these luxuries overkill. They can add weight to the pack, and what seems like a logical organizational system can quickly dissolve into a chaotic mess by day two or three, making it harder to keep things organized rather than helping. Increasingly, Hyperlite packs have become commonplace with experienced racers. They are costly, but they hold up better than any other pack when bushwhacking, and they are water resistant. They are minimalist in nature, so they require a different approach to organization, but some find that simplicity more efficient during the race. Packrafts. Packrafts are becoming a commonplace discipline in adventure racing, even at the 24-hour level. At the 2023 Endless Mountains, all paddling will take place in packrafts. Few packrafts are “cheap,” but it’s worth knowing that this is one piece of gear for which investment really translates to performance. When considering this investment, it might seem like a good idea to save a couple of hundred bucks on a boat, but many racers end up selling entry-level boats and upgrading to a better one after their first race or two. If performance and durability are not important to you, and you don’t mind some added weight, there are various options for lower-end rafts. Just make sure you do thorough research on alternative rafting companies. Mountain Bikes. Presumably, you are already the proud owner of a quality mountain bike. If you are considering upgrading or you are jumping into the deep end with an expedition race as one of your first events, here are some things to consider if you are in the market for a bike:

Bike Bags. Many experienced riders try to shift some of their weight onto their bike frames, especially during expedition races. This preserves your back and helps you conserve energy as you may be carrying large packs, larger quantities of food than in a shorter race, or a bit of extra gear to relieve a tired teammate. True, your uber-light bikes will no longer be featherweight, and your heavier bikes may become small tanks, but it really can make a massive difference to your performance and overall speed and endurance over the course of a multi-day event. We are partial toward the US-based company Dirtbags Bikepacking, who supports Rootstock Racing and is sponsoring the Endless Mountains, but there are other manufacturers out there. We like Dirtbags because they specifically design their products for long-haul bikepacking, which we find mimic multi-day adventure racing. Regardless of what company you go with, look at handlebar-mounted bags for easy access to food and small items and seatpost bags to store bigger gear. Some racers also like racing with a frame bag. Consider, too, how you will keep gear in those bags dry (some are waterproof, but many are not). odds and endsThis list could balloon into a small encyclopedia, and the reality is there are a million different items that racers use in multi-day racing. You will find all sorts of brilliant tricks, and what you believe you need on the race course will likely differ from your teammates and other racers on the course. That said, here are some random items to consider packing in your pack, bike box, or gear bin.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed