|

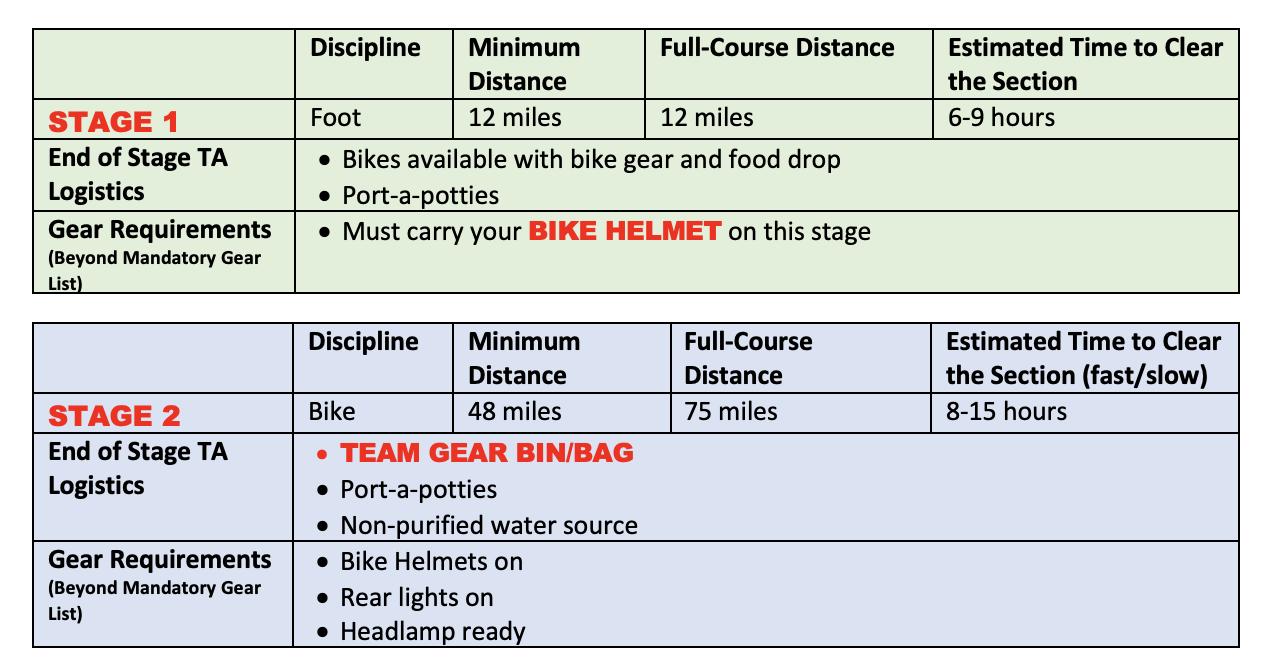

If sleep strategy is the fifth discipline of expedition racing, transitioning is the sixth. For some teams, it may also be the most important. Consider the following: Let’s say your race has seven transition areas (FYI, many expedition races have several more TAs than that). A savvy, experienced team may be able to average 15-30 minutes in any given TA – let’s call it 20 minutes for the sake of easy math. Some may be even faster, especially early in the race (and excluding sleep strategy). This team will spend 140 minutes in transition over the course of the race. Now, a less experienced team rolls into their first transition. They are exhausted and hungry. They haven’t fine-tuned their strategy or honed their bike breakdown. It’s not uncommon for a team like this to spend 2 hours or more sorting and swapping out gear, changing shoes, refueling, changing clothes, and repacking. Compound that over seven TAs and that’s 840 minutes – 14 hours of race time, more than half a day. In a race with shorter stages and more TAs, it’s not unheard of for less experienced teams to spend 18-24 hours in transition. These lost hours can dash podium hopes for pointy-end races. They can derail full-course dreams for mid-pack teams. They can cause teams to miss time cutoffs, and they may be the difference between officially finishing and not. TAing is a skill that top teams work at tirelessly and endlessly. Adventure racing is all about efficiency, and efficient TAs mean “found” time to spend on the course. So, how do you get there? Pre-raceSometime before race week, you will likely receive a race planner or schematic from the RD. These planners are always a bit different, but at a minimum they tend to provide teams with distance estimates and time estimates for each leg of the race. They will typically offer the order of stages and disciplines, and many will provide specific details that help with planning, strategizing, and packing. Such details may include what amenities are available at specific TAs and what bins, boxes, or bags you will receive. In a sense, the race has begun once these planners are distributed, and experienced teams will spend hours and hours working individually and as a team to prepare for the race at home: coordinating gear, planning for food and transitions, and organizing TA bags and bins. Obviously, you won’t have all the information you will need, but you can do a considerable amount of prep work, saving you time and energy during registration and in those precious hours on site before the race begins. This effort can be compounding. The hours spent at home studying that schematic and applying what you can to gear, food, and clothing prep will translate to better preparation, less stress, more sleep, and fewer mistakes at race HQ before the start. You will then have more time and peace to adapt as you learn more of what to expect from the event. And the next thing you know, you are hours and hours ahead of other teams who didn’t do this important work. When examining pre-race schematics, take note of the following:

ACTION ITEM: Talk with your team. What do you think is realistic based on the information you have and your team’s collective abilities? Estimate the time you expect to be on that leg. Pack a food bag and clearly label it for that stage of the race. Set aside any clothes, shoes, or gear you might want for that specific leg.

ACTION: Use this information to identify whether you will need to work harder for water. You don’t want to get stuck banking on hydration only to find there is none. You should also use this information to plan for hot meals or drinks that requires water. Pack your stoves, meals, and other gear into the proper bag, bin, or box.

ACTION ITEM: If the RD is offering food themselves or arranging it for purchase, plan to take advantage of it. Race food, no matter how thoughtful and tasty, tends to get old long before you reach the finish line, and taking advantage of provided calories or food and drink for purchase is well worth the money. Make sure you have sufficient cash and credit cards safely packed for the race. And know when those calories will be available to minimize overpacking food you won’t need (or want).

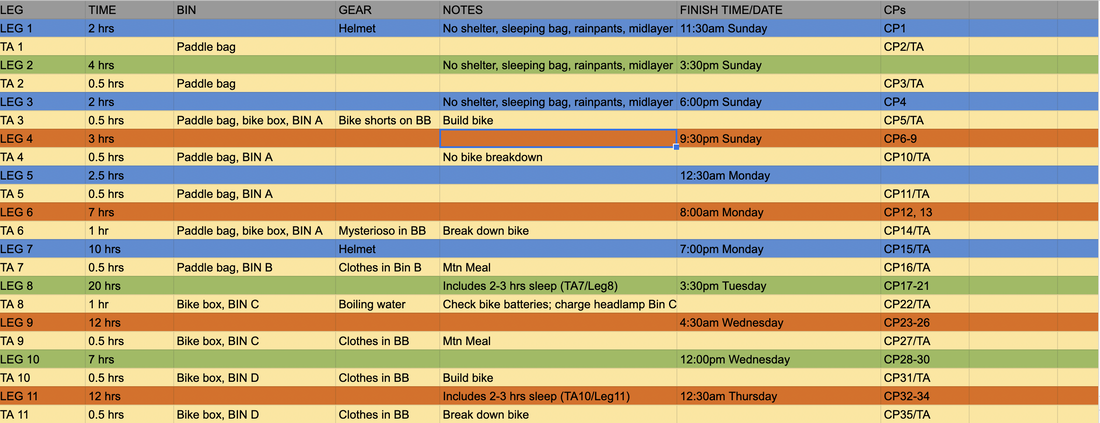

ACTION ITEM: Build a spreadsheet or some sort of organizational aid to help. It all starts with these bags and bins. Knowing exactly where you will see them and roughly when will then inform the rest of your pre-race packing. Making food bags, clearly labeling them, storing them, etc. Talk as a team. This may be one of the most important things you do before racing, getting to know each other aside. Triple check all of it.

good opportunity to practice that old adage, KISS: Keep It Simple, Stupid. Big zip-locks are your friend. Being able to see what’s in your bags can increase efficiency and reduce the need to use precious mental energy, sorting through which bags to grab on Day 4. Now you are racing...If you have done well planning, organizing, and packing your bins and bags, the real key to race-week execution is in communication with your teammates. Use the last thirty minutes of each leg to talk about the upcoming TA. What stage are you going to embark on? What gear will you need? What food needs resupplying? As you come into TA, you should consider the following tasks, depending on what the next stage might be.

Finally, as much as we privilege efficiency, there are times when TAs should serve as a legitimate break. Sometimes, you need to slow things down and do some quality work preserving a teammate’s mental or physical health to be able to continue. This is the razor edge of adventure racing: balancing the desire to maximize every minute and keep things moving and the need – sometimes – to slow it down or even stop, knowing that a couple extra hours of preservation might translate to hours gained later on the course or a more realistic chance to finish, or even win, the race.

1 Comment

Let’s face it: adventure racing does not make for pretty feet. Even in day-long races, you’re spending significant time on your feet, and even when you aren’t, you’re likely feeling the effects of the grime and wet you’ve subjected them to. In a multi-day race, the soreness, the blisters, and the abrasions will be compounded. So, what can you do about it? (Note: we're going to refrain from photos in this one!) pre-raceFirst, spend time on your feet. This means more than just getting out for long runs. Hit the trails with a pack. Add some weight. Mimic the gear, food, and water you will haul during the race and toughen those feet up. Second, do a little bit of learning. Read, watch videos, and familiarize yourself with first aid items and strategies to treat blisters, manage infections, and bandage wounds. It’s not a bad idea to practice blister bandaging and experimenting with dressings to see what works and what actually stays on when you get out in the woods. Youtube is a great place to learn different techniques. Gear up |

| Leaving TA, we had the luxury of being in a small village…and there was a local hotel. One teammate mentioned the possibility of getting a room. On several previous occasions, we had checked into a hotel in the middle of a race when the opportunity presented itself and when the timing was right. A few hours in a warm bed, out of your wet race gear, free from distractions like TA noise, traffic, or general sounds of the world does wonders for your next 24 hours of racing. Some of our teammates have even indulged in a hot shower. Imagine a hot shower when your body is worn down and potentially near pre-hypothermic levels! |

In that unnamed five-day race, another teammate scoffed.

“We aren’t out here to sleep in a hotel,” they said.

We then “slept” on a cold concrete bus platform two blocks away, shivering for an hour or two…

We know adventure racers enter the woods to test themselves against the elements. We also know that a long, cold, dark bike stage will always be more enjoyable if it follows a couple hours of sleeping in a comfortable and warm spot.

| That may mean a hotel. It may mean a barn, an abandoned bunk house, a utility shed, a u-haul trailer, a ski hut, the floor of a public restroom, or a heated covered wagon. We have encountered and slept in each of those places at various points in our adventure racing career. We know many other teams with similar stories. |

Time and again, the more rested teams take advantage of the rest of the field’s fatigued states as multi-day races wear on. Where you sleep really can make a huge difference.

Some other considerations on this point:

Some other considerations on this point:

- When pre-race planning, try to project where you will be during the nights. Are there towns? Houses? Structures? Campgrounds? Other potential legitimate shelter? Barns, trailers, containers, bathrooms? Try to identify possible target sites that roughly match up with your time projections and route, knowing you will surely need to adapt at some point.

- Plan for warmth. In 2015, we competed in the incredible Expedition Alaska. It was the last time we competed in an expedition race without some sort of ground insulation. Few races require this equipment, but what a difference it can make. As always, we all want to cut weight, but this addition to our packs has made a big difference for sleeping comfort and efficiency. We carry an ultrathin and light foam pad. It folds right up and weighs a few ounces. And it works well enough to keep us considerably warmer when sleeping. If you have spent enough time in the outdoors, you likely know that hypothermia can strike on a warm summer day… or night. Some studies suggest that more people succumb to it during the summer than the winter, because they enter the wilderness less prepared for the variable conditions. A wet sleep on uninsulated ground during a lukewarm summer night can and will suck warmth right out of your body. Stay there long enough, and your race is over.

- When you can, sleep at night. It’s not always possible, but even when you’re sleep deprived, your team will likely collectively sleep better in the dark than daylight. Circadian Rhythms and all. Sleep science is an enormous rabbit hole, especially when combined with REM Cycles, that raises all sorts of interesting questions about the ideal time and length to sleep. We’ll leave the heavy research to you, but know that natural sleep (quiet, dark, measured blocks of time) is way more effective than unnatural sleep (high noon, no shade, traffic going by) at helping you maximize your rest and positively impact your performance and overall experience.

myth #3: 15 minutes, when someone needs it, is enough

There are times when a quick nap IS enough, but anyone who has studied sleep or who has experienced sleep deprivation knows that fifteen minutes here and there might be enough to keep the train inching along, but it’s almost never enough to get that train cruising for a sustained period of time. It’s appropriate when you just need to get to the end of the leg and the wheels are coming off, but it should not replace more legitimate sleep.

Let’s take the legendary Kiwis from Avaya/Seagate as an example. They tend to race through night one, but they then settle into banking sleep most nights, if not every night, thereafter. Often a couple or even several hours of sleep at a time. Their race resume speaks for itself.

Let’s take the legendary Kiwis from Avaya/Seagate as an example. They tend to race through night one, but they then settle into banking sleep most nights, if not every night, thereafter. Often a couple or even several hours of sleep at a time. Their race resume speaks for itself.

| We, too, have found this strategy to be useful and often shoot for blocks of three hours, plus or minutes, pending on the race, situation, and time to the finish line. Itmay not work for everyone, but every time we have raced a multi-day event since adopting this strategy, we find we really come into our own later in the event. We sometimes let teams pass us, but we have found that we catch back up and then put time on those teams as the race progresses. It doesn’t always work in that the time of day may not be ideal or we struggle to find an appropriate place to stop, but planning where we might sleep starting on night two is always a major priority for us. |

myth #4: ta's are the best place to sleep

Sometimes they are! But often they are not. True, you may have the luxury of better access to sleeping gear (tents and sleeping bags if you don’t have to carry them on course, inflatable sleeping pads, inflatable pillows, etc.) and you will be near your gear bins, so extra food and clothes will be available.

| That said, even quieter TAs often have a fair bit of activity. Teams come and go, and volunteers and vehicles are often in constant motion. Many TAs tend to be in busier locations: parking lots, public facilities, etc. You are often in TAs at inopportune times to sleep (middle of the day, for instance), and it’s not uncommon for some members of the team to experience a jolt of energy and adrenaline while in TA, making it impossible to take advantage of the down time. |

Sleeping out of TA comes with different challenges (mostly related to what gear you have with you to sleep comfortably and where you will decide to physically lie down), but most experienced teams avoid TAs if there are other options. For other options, review Myth 2!

final thoughts

Like anything with AR, there is no right way to approach sleep strategy. The reality is, your team will experience highs and lows with sleep, regardless of how well you plan it out ahead of time. One teammate will be asleep on their feet and the others will be wired. Two people will bank some good sleep on night two, but the rest of the team will toss and turn and “wake up” more tired than when they laid down. You will make a bad decision or be forced into an unplanned sleep that isn’t restorative or productive. You will need to be flexible and adapt, knowing that the best laid plans may be immediately ruined by a navigation error that delays you by several hours, disrupting your entire plan for multiple nights of sleep.

Still, planning and strategy can go a long way. Talk as a team and approach sleep as the fifth discipline of expedition racing after running, biking, paddling, and navigation. We’ll leave you with some final nuts and bolts to toss around as you plan for this added challenge:

Still, planning and strategy can go a long way. Talk as a team and approach sleep as the fifth discipline of expedition racing after running, biking, paddling, and navigation. We’ll leave you with some final nuts and bolts to toss around as you plan for this added challenge:

- Earplugs and eye masks (or buffs) help light sleepers, especially during a daytime sleep.

- Caffeine helps. But it shouldn’t replace sleep in a true expedition race.

- Set multiple alarms. One likely won’t be enough.

- Consider your gear before sleeping, especially if sleeping in a TA. It usually makes sense to have everything ready BEFORE you sleep. Afterwards, you will likely be a mess. Easier to get things ready before sleeping and then just wake and go. And even that is harder than it sounds.

- Eat and drink before sleeping. A lot. Give your body a chance to use that fuel to better repair itself. You’ll still be exhausted, even after a few hours of sleep. Don’t deplete yourself, too.

- Get dry. This may not be possible, but try to find a dry location and get into dry clothes.

- Insulate. Dry clothes. Fleeces. Rain gear. Space blankets and emergency bags. Sleeping bags. Whatever you can do. If you don’t have a ground pad, is there any way you can get off the cold ground? Remember, even in warm weather, the ground will drain the heat from your body. Hypothermia sets in when your body temp falls below 95 degrees Fahrenheit. Even in the summer, the ground is reliably colder than that.

- It’s basic, but sleep at night. Not only because of all the scientific reasons to do so, but also because night is the hardest time for racing. Navigation is harder, technical travel is slower, there is less to look at and engage you, and darkness will wreak havoc on your mind. Burning three hours of good daylight to sleep is not efficient.

- When you can, elevate your feet when you’re sleeping. More on foot care in our next edition, but sleeping with your feet up can do wonders for inflammation!

| Finally, support each other. Pushing a teammate past their breaking point is not only unsafe but it also a sign of poor teamwork and likely won’t help your team reach the finish line. Forcing an overly-exhausted teammate to press on may fracture relationships. It also won’t help you as much as you think when it comes to maintaining steady forward progress or a fast |

pace. Take care of your teammates; if this means sleeping, whether it be a maintenance nap or a strategic big block of rest, do it.

You enter the woods for the love of the journey, in all its highs and lows. It’s much easier to enjoy that journey when you are in a good mood, sharper with your navigation, and moving efficiently. Without sleep, it’s much harder to really enjoy life. Race or not.

You enter the woods for the love of the journey, in all its highs and lows. It’s much easier to enjoy that journey when you are in a good mood, sharper with your navigation, and moving efficiently. Without sleep, it’s much harder to really enjoy life. Race or not.

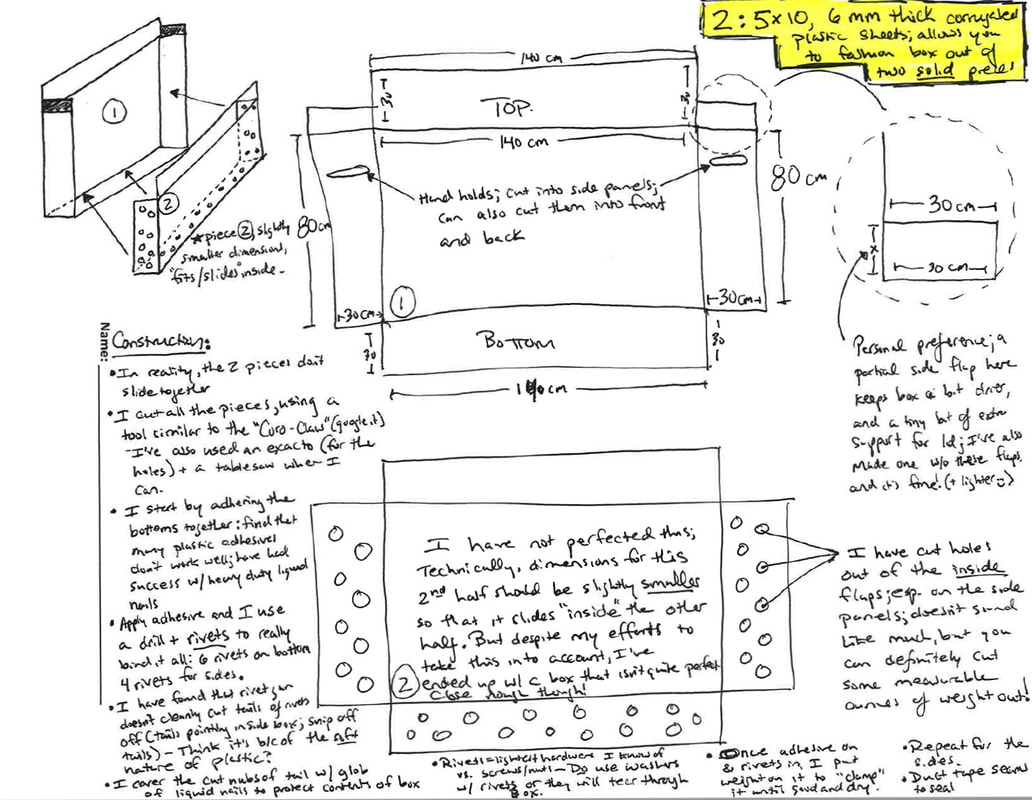

For new expedition racers, bike boxes can freeze you in your tracks, especially if the race you're eyeing requires standard dimensions from the Adventure Racing World Series. Unfortunately, you can’t walk into a local bike shop and buy one, and this is one thing Amazon likely won’t stock…we don't think …actually, it looks like they sometimes do, but as of this writing, they aren't available...we digress...

Walk around a transition area or peek into the back of the RDs' U-Haul at most expedition races and you will find a real hodgepodge of bike boxes. Most notably, you will see that many, perhaps most, are, in fact, hand made. So, where does one begin?!

Walk around a transition area or peek into the back of the RDs' U-Haul at most expedition races and you will find a real hodgepodge of bike boxes. Most notably, you will see that many, perhaps most, are, in fact, hand made. So, where does one begin?!

Pre-Made Boxes

At one time, Crateworks fabricated a bike box that met ARWS dimensions. As of now, they seem to have stopped production on those boxes. Those boxes were not cheap, and they typically didn't seem to hold up as well as some of the better built DIY boxes -- not because the quality of the boxes was poor, but because their ability to break down meant that there were more moving parts, which caused more wear over time than with some firmer less flexible boxes.

Still, you didn’t have to put time and labor into building the box yourself, and they were designed to break down, fold flat, and store easily. If you don’t mind spending a bit more, then an option like this is an easy solution.

The team from Rogue Adventures in Australia offers a list, which they update periodically, of outfitters currently producing bike boxes. Keep in mind you likely will pay for the box and shipping.

The DIY Box

OK, so you are going to go it yourself. Here’s what you need to know:

DIMENSIONS. As noted above, plan to build your bike box to ARWS dimensions: 140cm X 80cm X 30cm. All ARWS events will use these standard dimensions. If you err on one side of the measurement, go small.

MATERIALS. You are looking for corrugated sheets of plastic. Some call this coroplast, others corflute. You can typically buy this in 5mm or 6mm sheets. We have used 6mm for our boxes, with good results. They are a bit sturdier, stand up better when traveling, protect your equipment to a higher degree, and have a long shelf life. We built ours eight years ago, and we haven’t had to do any repair work. Getting your hands on such sheets is the real trick as they can be hard to find. We have had luck at a local sign shop like this, which has stocked sheets of coroplast or has been able to order them, and we have ordered two 5x10-foot sheets per box.

You will also need a heavy-duty bonding agent that will work on plastic surfaces, and you will need something to secure sheets together. We have used rivets and washers, which have worked well for us. They don’t weigh as much as other hardware, and with proper washers, they have held up without needing to be replaced. That said, you will need to invest in a rivet gun. We know other racers have had success with their own fastening systems. Ask around.

You will need some basic tools: X-acto knife, a tool designed specifically for cutting coroplast (you can live without it, but it makes some of the cutting much easier and cleaner), a drill, a rivet gun (if using rivets), or other tools if using a different fastening system.

Finally: when cutting the plastic sheets, consider the surface you are cutting on. Make sure it is a surface that can be marred by the X-acto blade, or use some cardboard to protect the floor. You will also need some heavy weight to help allow the adhesive to set. Finally, make sure you have plenty of time. You will likely need a fair bit of it to complete the project, including multiple time blocks to apply the adhesive and let it dry. Don't wait until race week!

Design

Before reinventing the wheel, the previously mentioned article by Rogue Adventure presents a great design with terrific instructions and is worth consideration.

Some racers have made clamshell style boxes. These boxes take more effort to design and build, but they open up nicely, and such boxes allow easier access to whatever is packed in the box. Ease of access can really make life seem so much easier on day four of an expedition race!

Our preferred model, however, is a simple variation of Rogue’s box. Check out the more detailed “blueprint” above for details. We prefer it for a few reasons:

None of this is to say these boxes are perfect or that you shouldn’t consider alternatives, but we like simple! As always, network: ask other racers what they use, what they have built, and why. What has worked well, what hasn't? Check out some different styles. Mix and match what works for you and what you like from various approaches.

In the end, you probably won’t save much in building it on your own, so consider whether it’s worth the time and effort. Just make sure you invest your money and/or time in something that seems durable. The worst is acquiring or building a flimsy bike box that either breaks down during the race or needs to be replaced or rebuilt a year or two later, and even worse than that is the weak box that doesn't do it's primary job: protecting your bike from damage during transportation.

Before reinventing the wheel, the previously mentioned article by Rogue Adventure presents a great design with terrific instructions and is worth consideration.

Some racers have made clamshell style boxes. These boxes take more effort to design and build, but they open up nicely, and such boxes allow easier access to whatever is packed in the box. Ease of access can really make life seem so much easier on day four of an expedition race!

Our preferred model, however, is a simple variation of Rogue’s box. Check out the more detailed “blueprint” above for details. We prefer it for a few reasons:

- It only requires two pieces of coroplast. You want to find the 5x10 sheets to make this work easily, but if you can land those, you can keep it to two sheets. You will essentially cut two halves of a box and connect them together. You can also use smaller sheets of corrugated plastic, but you will likely have to purchase more than two sheets and will probably pay more per square foot.

- Because the box is only two sheets, it is quite sturdy. There are fewer open/bonded seams to seal and fail. As noted earlier, our boxes are approaching a decade of use, and we have yet to do any repair work on them.

- Our boxes do not rely on heavy duty straps and do not include wheels. We have never had need for either, and the simpler the box, the lighter it is, meaning more weight allowance for bikes and gear when flying to and racing in an event with weight restrictions.

- When folding seams, use a board, or something straight to help make the seam. If you fold the plastic poorly, you can weaken the structure. Folding “with the grain” is relatively easy. Folding “against” it is harder, and there is an increased chance of a bad fold. For some of the longer folds, it can be useful to fold with a partner.

- On that note, when cementing, riveting, and generally working to construct the box (once you have measured, cut, drilled holes for rivets or other hardware, and prepared the box to build), it can help to work with a partner.

- It probably is overkill, but in the blueprint, you might note “holes”. The bottom and end caps of the box are double-sided. We cut holes out of the interior sheet of plastic. It might seem inconsequential, but we estimate it saved us a pound or two by doing so. That’s one more pound of food or an extra dry shirt or two for that low moment in the race. Every little bit counts!

- Install the heavy duty Velcro on the inside-top flap.

- Consider your grips for carrying. Some install ropes or other handles. No problem with that, but if you haven’t figured out our approach: we don’t want to add weight to the box if possible. We cut hand-wide slots on the end caps, and we also have cut slots on the sides. Grips on the ends are great if carrying the box with a partner or if you are taller than a hobbit (alas, we are not). Cutting holds on the sides allows one person to carry a box on their own.

None of this is to say these boxes are perfect or that you shouldn’t consider alternatives, but we like simple! As always, network: ask other racers what they use, what they have built, and why. What has worked well, what hasn't? Check out some different styles. Mix and match what works for you and what you like from various approaches.

In the end, you probably won’t save much in building it on your own, so consider whether it’s worth the time and effort. Just make sure you invest your money and/or time in something that seems durable. The worst is acquiring or building a flimsy bike box that either breaks down during the race or needs to be replaced or rebuilt a year or two later, and even worse than that is the weak box that doesn't do it's primary job: protecting your bike from damage during transportation.

The age-old adage of expedition racing is that the hardest part is getting to the start line. For many, the puzzle of packing gear, shipping or transporting it, and transporting yourself is the least enjoyable part of the experience, even if it’s not TRULY the hardest! But don’t let this logistical hurdle stop you; good planning and attention to detail goes a long way to helping minimize that stress. With almost no exceptions, you will fall into one of two categories: you will drive to the race, or you will have to fly.

Driving

On one level, drivers have it easy. No flights to contend with, no mathematical conundrums as you sort out weight and bag limits for bike boxes and gear bins, no questions of whether to fly with a gear bin or acquire one on site. And it’s a lot cheaper! On the other hand, for a race like the Endless Mountains that requires racers to use ARWS standard bike boxes, it can get tricky figuring out how to transport the bike box to the race.

For better and worse, there isn’t too much to say on this front. It’s really about the bike boxes, assuming the rest of your gear will fit in the car. Some have bike boxes that fold up and might be able to lay flat in the car. Easy. For those with rigid boxes, here are your options:

On one level, drivers have it easy. No flights to contend with, no mathematical conundrums as you sort out weight and bag limits for bike boxes and gear bins, no questions of whether to fly with a gear bin or acquire one on site. And it’s a lot cheaper! On the other hand, for a race like the Endless Mountains that requires racers to use ARWS standard bike boxes, it can get tricky figuring out how to transport the bike box to the race.

For better and worse, there isn’t too much to say on this front. It’s really about the bike boxes, assuming the rest of your gear will fit in the car. Some have bike boxes that fold up and might be able to lay flat in the car. Easy. For those with rigid boxes, here are your options:

|

- If not, consider shipping your box. We have had good luck shipping boxes domestically, with the bike packed safely inside. That said, if you are nervous about that option, you can ship a box packed with other gear, like clothing and food, or simply pack it with filler, and then transport your bike on a traditional bike rack. If you ship your bike through a service like FEDEX, consider opening an account as you can save money and more easily track your bike. Also, take special care to pack your bike well (more on that in the next Expedition Playbook post).

- You might also think about whether it might be worth renting a team U-haul or a trailer.

- Finally, try to network. There are a considerable number of racers with sprinter vans or trucks; it’s usually not that hard to find a willing helper, especially if it’s not for the whole team.

FLYING

For those flying in from further afield, you have harder logistics. Notes about bike boxes above still apply: how are you going to get all your gear and bike boxes to the airport? How to deal with weight restrictions? How to pack everything without paying the airline a small fortune in extra fees? Here are some tips to consider when flying to you race:

| 1)Give yourself time to pack and repack. Lay out all your gear. Obviously, prioritize what is mandatory, and set it aside. In this pile you should include clothing that you will absolutely, definitely want to wear. That gear is non-negotiable. Then lay out all of your other gear: all of your food, extra clothes, extra shoes, extra equipment that MIGHT be useful. Keep these items in a separate pile initially so you can easily adjust if you find you have too much gear. Prioritize from there until you are forced to leave things out. And remember, at most events you can always buy food on site. More on that below. |

2)Make sure you know what you are allowed to bring on the plane. How many checked bags are you allotted? Carry-ons? How much does each bag cost? Weight restrictions? Size limits? If you have disposable funds, this isn’t as stressful, but if you have a tighter budget, micromanaging each pound becomes important. Know what you are allotted.

1)What is your airline’s policy on bikes? Some airlines have started to allow for the free transportation of bikes, but make sure you know the associated costs, weight, and size restrictions you are dealing with. And read the fine print. Not all routes are treated the same.

2)Airport to race HQ: this often is the hardest puzzle to fit together. Flying and transporting gear is tedious, but you will either figure out what to leave at home for financial reasons or you will shell out for that extra bag. When you land, how do you – and your gear – get to race HQ? Start off by studying the race website. Some RDs include pre- and post-race transportation in the race fee. Others include it as an add-on. Some don’t offer any assistance at all. If the website isn’t clear, reach out to the RD. Some of the best races we have done offered no transportation perks, so don’t let that deter you. That said, make sure you are planning WELL ahead of time to avoid paying extra or ending up stuck without any apparent options to get to and from the race.

3)If your race does not include transportation assistance, consider the following:

1)What is your airline’s policy on bikes? Some airlines have started to allow for the free transportation of bikes, but make sure you know the associated costs, weight, and size restrictions you are dealing with. And read the fine print. Not all routes are treated the same.

2)Airport to race HQ: this often is the hardest puzzle to fit together. Flying and transporting gear is tedious, but you will either figure out what to leave at home for financial reasons or you will shell out for that extra bag. When you land, how do you – and your gear – get to race HQ? Start off by studying the race website. Some RDs include pre- and post-race transportation in the race fee. Others include it as an add-on. Some don’t offer any assistance at all. If the website isn’t clear, reach out to the RD. Some of the best races we have done offered no transportation perks, so don’t let that deter you. That said, make sure you are planning WELL ahead of time to avoid paying extra or ending up stuck without any apparent options to get to and from the race.

3)If your race does not include transportation assistance, consider the following:

- Car rental. Remember, you have multiple teammates, which means you need to transport one or two large duffels per person, and you will have up to four bike boxes. That’s a lot to transport. You may need to rent multiple vehicles. Many racers have rented vans or trucks to move all their gear to HQ. Some have rented multiple vehicles.

- Ask. Even if the RD isn’t offering assistance, email them. They often know people who are well positioned and ready and willing to help, especially if you are traveling from overseas.

- Network. Post to the event website or on local discussion boards. In two of our races in the UK, we have connected with wonderful local racers who have graciously helped us with airport pick up and gear transportation. We rented our own car to travel about and make grocery store runs, but they helped us get our bearings and handled our bike boxes. There are almost always local racers willing to help, and they are likely to have the means to help you store and transport gear to the host site. Network.

- Ship your bike. FEDEX is a well-tested option, and there are also bike-specific services such as Bike Flights. It may not necessarily save you money on your gear, but it may allow you to rent a cheaper car. This may create bigger logistical challenges when racing internationally, but domestically, it may be worth exploring.

- Bike rentals. This often comes down to personal preference. Few experienced racers risk renting a bike that isn’t their own, but it happens. Some have gotten lucky and rented quality bikes. Others, less so. To some degree, it’s what you are willing to pay for. Renting a bike may not save you any money, but it will make travel easier. Keep in mind that you will likely still be required to have a bike box. Here, too, reach out to the community through the RD, race page, or a group like AR Discussion Group; you may be able to borrow or source that locally.

packing

Okay, you have sorted your logistics, you’ve done the training, you’ve spent your holiday money on new gear, and now you need to pack. On one level, this is straight forward: lay out your gear, organize it, check it two or three or seven times, and then throw it all in some bags and boxes and do it all over again when you get to your pre-race lodging.

If you can drive to the race, you are fortunate in that you don’t need to worry too much about overpacking. That said, we like to think of packing as the first stage of the race. This is your first chance to really start thinking about what you are going to need. How you are going to pack your actual race pack? How will your your team distribute mandatory gear? What goes in your bike box? A gear bin? What stays in your pack? How many pairs of shoes do you REALLY need, and is it worth using leftover weight for clothes, food, or something else?

Experienced teams show up to the race with a much better handle on their gear. Their food is often already organized into twelve-hour bags, or something that works for them individually. Clothes are packed and organized. Typically, you will receive some sort of race planner from the RD a week or so out, and the savvy racer will figure out how much food, clothing, and other gear will be required on each stage. They will organize that gear at home, label bags for each stage, and save themselves hours of time at the race site before the race starts. This translates to more sleep and less stress.

If you can drive to the race, you are fortunate in that you don’t need to worry too much about overpacking. That said, we like to think of packing as the first stage of the race. This is your first chance to really start thinking about what you are going to need. How you are going to pack your actual race pack? How will your your team distribute mandatory gear? What goes in your bike box? A gear bin? What stays in your pack? How many pairs of shoes do you REALLY need, and is it worth using leftover weight for clothes, food, or something else?

Experienced teams show up to the race with a much better handle on their gear. Their food is often already organized into twelve-hour bags, or something that works for them individually. Clothes are packed and organized. Typically, you will receive some sort of race planner from the RD a week or so out, and the savvy racer will figure out how much food, clothing, and other gear will be required on each stage. They will organize that gear at home, label bags for each stage, and save themselves hours of time at the race site before the race starts. This translates to more sleep and less stress.

If you are flying, you will have to contend with weight restrictions unless you fork out for extra baggage. Assuming you don’t do that, consider the following tips for packing your gear to fly:

- As you pack, weigh your gear. You will have weight restrictions for the flight and for the race, typically 50-55 pounds per bag and bike box at the event. Try to keep your gear within those bounds. We typically fly with a large duffel and a bike box for each team member. So, approximately 100 pounds per racers, not including our carry-ons. A basic bathroom scale will do, or you can invest in a portable digital hand scale. These scales are handy, since you can bring them with you. They allow you to make quick adjustments at the airport, and they help you and your team pack your gear ahead of times to make weight restrictions.

- Certain gear should go in your carry-on. Lithium battery lighting systems should come with you to comply with federal requirements. Beyond that, if you smaller items that you can’t afford to be without – other lights, heavier food – add those to your carry-on. Assuming your race pack is rated to handle the load, that’s a good option for your carry-on bag. One less thing to stow underneath.

- On the flip side, some gear – knives, always; paddle shafts and trekking poles, sometimes – should go into your checked bags so as not to get flagged by security. Play it safe and pack these items in a bike box or checked bag.

- And some gear, like CO2 cartridges or gas canisters for a cooking stove, technically can’t fly at all.

- Many experienced racers know that it’s not worth packing all of your food when you can hit a local supermarket before the race. This means that you want make sure you have a sense of what will be available. Especially if you are racing overseas, don’t expect to find that specific energy bar or gel, in a local market. Is there even a local market available? Will you have time to go shopping? Even some more basic grocery items may not quite be the same. Some popular race food, such as chips, candy bars, and crackers, is generally universal, but try to get a sense of what you will find locally and be prepared to be flexible. Once you’ve done your homework on this, by leaving some relatively basic food at home can be a nice way to lighten your load, and for the record: we have always found some time to hit a local market or grocery before the race. It might mean arriving a day earlier, but the more time to settle in, the better.

- When packing your bike box, keep in mind that TSA may open up your box after you leave it with them. You should definitely pack more gear in with your bike to maximize the weight allowance, but know that airport officials will potentially poke around. It’s usually not a big deal, but we advise making things as easy as you can for them, both so that they can explore without going through lots of little items and also so they repack when they are done.

- On this note, consider how you seal your bike box. If you use something like duct tape, TSA might cut through it and do a poor job resealing your box. We have installed heavy duty Velcro on our lids that will keep the box closed. We also use a few short strips of duct tape as a backup, knowing that it’s not the end of the world if TSA cuts those strips rather than peeling them back. In short, when packing bike boxes: plan for the worst when it comes to overzealous TSA agents examining the contents of that gear.

One final tip, from brent...

Who is the nicest, friendliest person on your team? I have a theory that if a team travels together and allows that person to lead the way in check in, your chances of saving some money with your bikes and bags go way up. For us, it’s Abby: granted, Abby and I always travel together when we’re both racing (and we are married), so it’s easier for one of us to check the other one in. But time and again, I shut my mouth and hang back. She talks to the desk agents about the race, the bikes, how exciting it is. And we often pay less than we expected. Sometimes they waive the bike fee. Sometimes they charge less for one of the bags or the bike. It doesn’t work every time, but usually we get a great deal!

Ask any experienced adventure racer, especially those who have experience in multi-day racing, and you will find that few people went into their first race with all the “best” gear. It’s just too much of an investment. Racers build their gear closet over time, investing in a new major item or two each year. Unless you have the disposable cash to buy every ideal piece of equipment at once, figure out what you really need and know that there are plenty of options to get by.

There is also a difference between the best piece of gear and the piece of gear that is best for adventure racing. That ultra-light $400 rain jacket? It will likely get shredded before you come out of the woods on your first monster overland trek.

Keep in mind that while online reviews are useful, most reviewers are not putting gear through the ringer the way expedition racers are. Your best bet is to do your research and pricing, and ask some experienced racers for their thoughts, too.

To begin, check out the article on gear in USARA’s “New to AR” Series. This piece explores the basics of a standard AR gear list. While it wasn’t written with expedition racing in mind, it is a good foundation for many of the basic gear requirements you will have for an expedition race.

Beyond that, here are some additional equipment considerations geared (see what we did there?) specifically toward expedition racing. Note that this post is a little bit more scattershot than some of our others. Gear is a big and unwieldy topic; we've organized it as best we can!

There is also a difference between the best piece of gear and the piece of gear that is best for adventure racing. That ultra-light $400 rain jacket? It will likely get shredded before you come out of the woods on your first monster overland trek.

Keep in mind that while online reviews are useful, most reviewers are not putting gear through the ringer the way expedition racers are. Your best bet is to do your research and pricing, and ask some experienced racers for their thoughts, too.

To begin, check out the article on gear in USARA’s “New to AR” Series. This piece explores the basics of a standard AR gear list. While it wasn’t written with expedition racing in mind, it is a good foundation for many of the basic gear requirements you will have for an expedition race.

Beyond that, here are some additional equipment considerations geared (see what we did there?) specifically toward expedition racing. Note that this post is a little bit more scattershot than some of our others. Gear is a big and unwieldy topic; we've organized it as best we can!

Clothing

Come to the race prepared for anything. A five-day race means the potential for diverse weather. While the PA mountains are not the Rockies, you may still experience wild swings in temperatures at the Endless Mountains Adventure Race. Late June in Pennsylvania can mean anything from cold rain to sweltering heat and humidity – often within a 24-hour period! Weather forecasts will help, but it’s wise to have options as things can shift during race week.

You’ll want to figure out what clothes you’re starting in and then what you’ll need for each subsequent leg of the race, and then you will want to pack strategically, based on the course schematic you will likely receive in the week or two preceding the event. Most racers store dry clothes in as many resupply bags, bins, or boxes as they can.

It should go without saying, but leave the cotton at home. Synthetic will dry faster, keep you warmer, and keep you cooler. When planning for cold weather, consider investing in merino wool. It’s a game-changer in regard to performance, and by all accounts it resists the stink that comes from five days of racing like nothing else.

shoes

| It’s easy to go light on shoes. That said, we recommend bring some extra if you have them and your weight allowance allows. Shoes can and will get saturated, full of grit, or even damaged during a multi-day race. Having fresh shoes to change into can assist with foot care and management and can make the difference between an enjoyable day three and a section during which it takes every ounce of focus and determination to keep those feet moving. Some people like to bring different models or sizes to have choices for later in the race, as their feet get blistered, sore, or swollen. |

Changing shoes can also help reduce the chances of blisters…or at least blisters that threaten your race. You may not be able to stage a fresh pair of shoes for every section of the race (though some people try to), and you may need to jettison a pair or two to keep your box or bin at weight, but try to bring at least an extra pair or two if possible.

Ta gear

When you’re planning your clothing, take TAs into account, especially the ones where you may end up sleeping. At a minimum, most experienced racers pack lightweight TA shoes. Crocs are popular: they are easy-on, easy-off, and they are airy, allowing your feet to dry out and recover a bit. Likewise, some people like to have an extra fleece or jacket, just for transitions. The longer the race, the harder it will be for your body to regulate temperature.

rain gear

Some racers invest hundreds and hundreds of dollars into an AR shell. Perhaps in a race with legitimate mountaineering or particularly cold temperatures it is worth it, but more often than not, a solid mid-range jacket will do. Keep in mind: an expedition race is relentless on gear. In an environment like you will encounter at the Endless Mountains, you will be off trail a fair bit - with underbrush poking, ripping, and grabbing at you and your gear. Consider how you will feel if that $500 jacket is damaged or lost during the event.

| You want quality jackets and pants, but between holes, openings, and sweat, this gear typically serves to keep you warm rather than bone-dry. As long as it can do that, you are good to go. This said, like with shoes, many seasoned racers will throw an extra set rain jacket and rain pants into their gear bins, in case there is an opportunity to legitimately dry out. |

Regarding rain pants: these are, in some ways, one of your most important pieces of gear. Not only do they help keep you drier and warmer, but they add a nice layer of extra protection when bushwhacking. In woods like those in the PA Wilds, it’s not uncommon to become saturated quickly when you’re bushwhacking. Even if the sun is out, overnight dew and rain can leave woods dripping with condensation and rainwater for hours. If it happens to be cooler, before you know it you will be soaked through and freezing. Rain pants can make all the difference in the world. Here, too, you may not remain entirely dry, but you will stay warm enough to keep racing comfortably.

Finally, we recommend avoiding minimalist rain gear, especially for an event like the Endless Mountains. It may save you a few ounces, but it likely will cost you a fair bit of money, and it will almost definitely get shredded right out of the TA.

Finally, we recommend avoiding minimalist rain gear, especially for an event like the Endless Mountains. It may save you a few ounces, but it likely will cost you a fair bit of money, and it will almost definitely get shredded right out of the TA.

big-ticket items

So, what gear should you strongly consider investing more money in? Here are some ideas, though remember, most people don’t drop their credit card on all these things at once. Consider what you want to prioritize and build your collection.

Lighting. The cheaper option here is to use lights that run on disposable batteries. These light systems tend to be less expensive, and you don’t have to invest in extra batteries or come up with creative ways to recharge. Most experienced racers invest in higher end set-ups, however. There are several great lighting companies including Lupine Lighting, Dinotte, Light in Motion, and more.

These systems produce more light output, and many, like Lupine can now be programmed to put out different lumens based on personal preference and comfort. Some racers race with one light throughout the race. Others have a different setup for bike sections. You want to consider battery run-time, weight, and lumens/light output when determining how to invest.

The Rootstock Race team has been supported by and races with Lupine Lighting, and we have been thrilled with the power, battery life, ease of use, and service options that come with the investment. We can't recommend them enough!

Paddles. Most seasoned racers are racing with two or four-piece carbon kayak paddles. Such a paddle can cost several hundred dollars, but they are much lighter and can break down for transport in your pack, which comes in handy if you have to carry paddles overland for a stretch. They are lightweight, which also means less wear and tear on your body. Multi-piece paddles also pack easier in paddle bags, and they take up less of your weight allotment.

Packs. Really, any pack will do, but you want something durable, functional, and comfortable. You will be wearing your pack(s) for several days, so make sure you have something that fits your body well, or be prepared for some serious chafing. Consider how you will pack your gear, what you want to access quickly, etc. Many racers love packs with endless side pockets for small items and food; others find these luxuries overkill. They can add weight to the pack, and what seems like a logical organizational system can quickly dissolve into a chaotic mess by day two or three, making it harder to keep things organized rather than helping. Increasingly, Hyperlite packs have become commonplace with experienced racers. They are costly, but they hold up better than any other pack when bushwhacking, and they are water resistant. They are minimalist in nature, so they require a different approach to organization, but some find that simplicity more efficient during the race.

Packrafts. Packrafts are becoming a commonplace discipline in adventure racing, even at the 24-hour level. At the 2023 Endless Mountains, all paddling will take place in packrafts. Few packrafts are “cheap,” but it’s worth knowing that this is one piece of gear for which investment really translates to performance. When considering this investment, it might seem like a good idea to save a couple of hundred bucks on a boat, but many racers end up selling entry-level boats and upgrading to a better one after their first race or two. If performance and durability are not important to you, and you don’t mind some added weight, there are various options for lower-end rafts. Just make sure you do thorough research on alternative rafting companies.

Mountain Bikes. Presumably, you are already the proud owner of a quality mountain bike. If you are considering upgrading or you are jumping into the deep end with an expedition race as one of your first events, here are some things to consider if you are in the market for a bike:

Lighting. The cheaper option here is to use lights that run on disposable batteries. These light systems tend to be less expensive, and you don’t have to invest in extra batteries or come up with creative ways to recharge. Most experienced racers invest in higher end set-ups, however. There are several great lighting companies including Lupine Lighting, Dinotte, Light in Motion, and more.

These systems produce more light output, and many, like Lupine can now be programmed to put out different lumens based on personal preference and comfort. Some racers race with one light throughout the race. Others have a different setup for bike sections. You want to consider battery run-time, weight, and lumens/light output when determining how to invest.

The Rootstock Race team has been supported by and races with Lupine Lighting, and we have been thrilled with the power, battery life, ease of use, and service options that come with the investment. We can't recommend them enough!

Paddles. Most seasoned racers are racing with two or four-piece carbon kayak paddles. Such a paddle can cost several hundred dollars, but they are much lighter and can break down for transport in your pack, which comes in handy if you have to carry paddles overland for a stretch. They are lightweight, which also means less wear and tear on your body. Multi-piece paddles also pack easier in paddle bags, and they take up less of your weight allotment.

Packs. Really, any pack will do, but you want something durable, functional, and comfortable. You will be wearing your pack(s) for several days, so make sure you have something that fits your body well, or be prepared for some serious chafing. Consider how you will pack your gear, what you want to access quickly, etc. Many racers love packs with endless side pockets for small items and food; others find these luxuries overkill. They can add weight to the pack, and what seems like a logical organizational system can quickly dissolve into a chaotic mess by day two or three, making it harder to keep things organized rather than helping. Increasingly, Hyperlite packs have become commonplace with experienced racers. They are costly, but they hold up better than any other pack when bushwhacking, and they are water resistant. They are minimalist in nature, so they require a different approach to organization, but some find that simplicity more efficient during the race.

Packrafts. Packrafts are becoming a commonplace discipline in adventure racing, even at the 24-hour level. At the 2023 Endless Mountains, all paddling will take place in packrafts. Few packrafts are “cheap,” but it’s worth knowing that this is one piece of gear for which investment really translates to performance. When considering this investment, it might seem like a good idea to save a couple of hundred bucks on a boat, but many racers end up selling entry-level boats and upgrading to a better one after their first race or two. If performance and durability are not important to you, and you don’t mind some added weight, there are various options for lower-end rafts. Just make sure you do thorough research on alternative rafting companies.

Mountain Bikes. Presumably, you are already the proud owner of a quality mountain bike. If you are considering upgrading or you are jumping into the deep end with an expedition race as one of your first events, here are some things to consider if you are in the market for a bike:

- 29-inch wheels tend to be the wheel size of choice in adventure racing because of the long cross-country nature of riding that is typical in the sport, though many racers also ride on 27.5.

- Lighter bikes mean less energy exerted in a multi-day race.

- Carbon is popular.

- While many racers do invest in full suspension, you’ll see a number of hardtails too. Typically, MOST riding in an expedition race is on relatively forgiving roads, forest roads, and relatively easy trails. It’s not to say you won’t see some rough trails and tracks, but many riders sacrifice some of the weight and cost of full suspension for a lightweight 29-inch hardtail. Totally personal preference there.

Bike Bags. Many experienced riders try to shift some of their weight onto their bike frames, especially during expedition races. This preserves your back and helps you conserve energy as you may be carrying large packs, larger quantities of food than in a shorter race, or a bit of extra gear to relieve a tired teammate. True, your uber-light bikes will no longer be featherweight, and your heavier bikes may become small tanks, but it really can make a massive difference to your performance and overall speed and endurance over the course of a multi-day event. We are partial toward the US-based company Dirtbags Bikepacking, who supports Rootstock Racing and is sponsoring the Endless Mountains, but there are other manufacturers out there. We like Dirtbags because they specifically design their products for long-haul bikepacking, which we find mimic multi-day adventure racing. Regardless of what company you go with, look at handlebar-mounted bags for easy access to food and small items and seatpost bags to store bigger gear. Some racers also like racing with a frame bag. Consider, too, how you will keep gear in those bags dry (some are waterproof, but many are not).

odds and ends

This list could balloon into a small encyclopedia, and the reality is there are a million different items that racers use in multi-day racing. You will find all sorts of brilliant tricks, and what you believe you need on the race course will likely differ from your teammates and other racers on the course. That said, here are some random items to consider packing in your pack, bike box, or gear bin.

- Toothbrush and toothpaste. Normally adventure racers scoff at luxury. But this one is more than that. Going for 24 hours without brushing is no big deal. But try racing for five days, drying your mouth out, and continuously eating. Your teeth won’t like it, and neither will your gums, tongue, and other soft tissues. It’s not uncommon for racers to end up with sores and discomfort in their mouths if they don’t attend to business. Pack a small toothbrush and tube of toothpaste. Some people prefer to do this in TAs, some like to do it while on course. Either way, even one or two brushings will keep your mouth healthier, which might also translate to much more comfortable eating!

- Foot Powder. We noted that you will want to keep a pair of crocs or something similar in your TA bins. Consider what other foot care items you might want to have with you in TA. Many racers use Gold Bond or similar powders to help dry out their feet.

- Map Boards. If you don’t already navigate with a quality map board, invest in one. You might find yourself out on an expedition race bike leg for 24 hours or more. Fighting with a map case dangling around your neck is not a distraction you will be able to ignore. We are big advocates for Autopilot (and we also are authorized distributors of their boards). Lightweight and easy to use, their biggest selling point is their attachment mechanism. There are many other great map boards out there, but many require legitimate hardware to attach and detach: nuts, bolts, wrenches, allen keys. On day three, you do not want to deal with this when building a bike. Autopilot map boards have quick releases and take about three seconds at most to mount and dismount.

- Sunscreen. Chapstick. Bug Spray. Again, in a 24-hour race, you may not bother with such items. But skin care and sun protection are crucial when you are going to be exposed for this long. Racers have dropped out of events from complications arising from poor body maintenance. Sunburn can lead to terrible pain, chafing, and blistering that can make racing extremely uncomfortable. The mental strain from this can undo the best racer and threaten a team’s ability to get to the finish line. Even if you do tough it out, it won’t be nearly as enjoyable as you would want it to be. Broken, cracked lips can make eating unpleasant, leading to a drop-off in calorie intake and ultimately bonking. Bugs tend to be more of a mental hurdle, but with the prevalence of tick-borne illnesses, there is good reason to bring along some bug spray as well.

- Extra Bike Repair Gear. Bikes are much more prone to unusual breakdowns in an expedition race than in a shorter event, and it’s wise to have the gear you need for basic repairs. Again, there are hundreds of odds and ends we could discuss, but here are some basic issues that come up with some frequency. You should obviously know what to do with such items if you are going to pack them!

- Extra bike cleats

- Extra bolts for bike cleats

- Extra derailleur hanger (make sure it fits your bike; there are some “universal” hangers that might work for your whole team, but be aware that not all “universal” hangers are actually universal!)

- Extra rear derailleur

- Extra bike chain links

- Super Link for your bike chain

- Small bottle with extra lube for the muddy days in the woods. Some people use Visine dropper bottles for this. Wrap it in plastic wrap so it doesn’t leak in your bike bag.

- Chain tool

- Extra bike tire for your TA bin

- Extra sets of brake pads (make sure they fit your bike(s))

- Tarp. If you have room in your bags and bins, a tarp can make for easier, cleaner transitioning.

|

- Instead of recharging and restoring, you end up in worse shape than you were before. Consider bringing two types of ground pads: an inflatable one that is largely for TAs, and a very thin, minimalist foam pad that folds up quite small and weighs a few ounces. You can carry the latter with you out on course and pull it out when sleeping on the ground.

- Ear plugs. Inflatable Pillow. Eye mask. Yes, you can get creative: use a buff for a mask. Stuff a pack under your head. That said, these are common items you will see in transition bags and bins that can make sleeping easier, especially if you are in a busy TA or sleeping during the day. Some people have no problem crashing out in a busy parking lot in the hot sun. But others, despite the exhaustion of a multi-day race, need some help. Bring what you need.

- Tums. Five days of racing and five days of endless eating tends to upset the stomach, and many racers develop heartburn. Something like Tums can help relieve such discomfort.

- Cooking Gear. Small stoves, Jetboils, pots, utensils. You’ll likely find hot food on the course to buy, but it’s always nice to warm up the camp stove when you hit a TA and make a hot meal. Look for the long-handled utensils for those deep pocket bag meals!

- Cipro. If you take care of yourself and filter your water, you should be alright. But you never know. Things happen when you are out in the woods for five days. Many experienced racers (and travelers) know that traveling with some backup antibiotics like Cipro can be useful in a real pinch.

- Other Medications. Don’t shirk this. This is a long, wilderness-based expedition you are taking on. Saving eight ounces by just bringing some Band-Aids, a few gauze pads, and a tube of antibiotic cream can set you up for a dangerous situation if you run into trouble. You will not bring all of this gear, but check out some wilderness first aid kit lists like this one from NOLS for ideas on what you might want, just in case. In addition, don’t forget personal meds like EpiPens, inhalers, or prescription meds that you need.

|

If you have competed in a 24-hour race, you have likely already identified some of the key roles you should consider when building or developing a team. There is no correct way to manage the question of roles. Some teams like to identify specific tasks that individual racers take responsibility for. Others have multiple people that all can and do serve in each role at any given time. Here are examples of some roles and responsibilities that can help you have a more successful first expedition race.

Captain

Many teams identify a team captain, and this role can be the hardest to define. Some teams believe a captain manages the overall strategy but shouldn’t navigate. Some believe the captain should play a primary role in keeping the team engaged, managing the team’s highs and lows. For some teams, the captain is purely a symbolic designation: they are the person who signs papers and goes to the pre-race briefings. Ultimately, captains are leaders, and there are so many ways to lead, especially in an expedition race. The key here is to clearly define as a team what this role should entail, and it is crucial to sort this out before race week. It can be difficult if the team “captain” is soft-spoken, easygoing, and relaxed for eight months leading up to the event but then turns into a drill sergeant in the woods.

Navigator

There are two primary approaches to navigation in a multi-day race. Neither one is right. Again, clear expectations ahead of time are crucial.

- Primary Navigator. For good reason, teams with a clear “best” navigator tend to have that person on the maps for the duration of the event. This said, navigating and staying sharp for five straight days is challenging, and primary navigators should be prepared to lean on a back-up navigator or two if the need arises. This might simply mean conferring with the team more when fatigue sets in. It might mean being open to passing the maps off for part of a stage or an entire stage. The primary navigator is responsible for knowing when they are tired and being humble enough to take a break if their fatigue is impacting their craft.

- Navigation by Committee. In this scenario, teams purposely divide up the navigation duties. You might assign legs to different people. This works well when you have multiple navigators who are evenly matched or when, for example, one person is better at bike navigation than navigating on the water. A drawback to this approach is that some navigators have a hard time picking up the maps “cold” in the middle of the race if they haven’t been serving as primary navigator from the start.

Mule

Traditionally, you will hear many adventure racers talking about a team mule (or two). These racers tend to be physically stronger and are generally responsible for carrying extra gear, shouldering a pack when someone might benefit from a break, or towing a teammate who needs some extra power. Be aware that some “mules” tend to overdo it, and regardless of how strong they are, they will have a low moment or three over the course of a multi-day race. Sleep deprivation, elevation change, weather, and nutrition, not to mention injury, can all impact a mule’s ability to haul that extra gear.

You need to keep the big picture in mind and make sure that the team keeps day four in perspective on day one when the mule is thinking about carrying three packs and three bikes while towing the whole team and chopping away thick underbrush with a machete to make up ten minutes of time. Ideally, you are open to everyone on the team muling at some point. It’s a long race, and the best teams (not necessarily the winning teams, but the most experienced, the best racers) know that everyone will shoulder a heavy load at some point in a multi-day race.

You need to keep the big picture in mind and make sure that the team keeps day four in perspective on day one when the mule is thinking about carrying three packs and three bikes while towing the whole team and chopping away thick underbrush with a machete to make up ten minutes of time. Ideally, you are open to everyone on the team muling at some point. It’s a long race, and the best teams (not necessarily the winning teams, but the most experienced, the best racers) know that everyone will shoulder a heavy load at some point in a multi-day race.

Mechanic

Ideally, have someone who will take lead with bike mechanicals. Many teams have one or two people who naturally enjoy tinkering with bikes and can fill this role. If you don’t, think about having someone take some basic bike maintenance and trail repair classes at a local bike shop or REI. Odds are good that you will need to deal with a flat tire, a broken chain, or a malfunctioning brake. Whether it’s the bike mechanic or someone else, make sure you also have some added bike repair tools and parts so they can do their job.

Medic

We believe that safety is of the utmost importance at Rootstock Racing, and while many races don’t require any medical training, every racer should recognize that they are thinking about signing up for a race that will have them in wilderness settings for days on end, often with no easy access, and they will be sleep deprived. Things happen, and being able to respond to and stabilize a situation is crucial. While we are requiring a WFA (Wilderness First Aid) certification for at least one team member at the Endless Mountains, WFR (Wilderness First Responder) is even better. Anyone spending significant time in the outdoors should consider such a certification.

Logistics Planner

Who has an eye for detail? Who are the strongest organizers? Who likes to make spreadsheets with food and gear schedules for each stage of the race? It helps to identify one or two people who can work to assist the team in planning for the race and stay on task in TAs. Of course, sometimes your “logistics planner” is a zombie and can’t stay awake, but ideally someone should coordinate the team to manage TAs efficiently and make sure that the team is carrying the gear and nutrition needed for a given portion of the race.

Motivator

You will struggle. Sometimes one person will be in a dark place. Sometimes the whole team may be. It helps to have some folks ready to lift the team in those moments - to get them going, keep them going, or boost morale. Songs, stories, riddles, games. This is a tough one as every team and every racer will respond to different efforts. Talk about individual preferences ahead of time. As with the captain's role above, it is useful for the motivator to know what helps each individual team member - or better yet, for everyone on the team to know what helps the other members brighten up!

Boatmaster

We've never actually heard or used this term, but it sounds good. So, we will go with it. Expedition races tend to incorporate more challenging paddling. Often times it’s harder, simply due to the sheer length of the stages. But you may encounter more white water, nighttime paddling, or, in some races, ocean paddling. Ideally, you will have one or two teammates more comfortable handling boats, team members who can handle the stern or pick lines through a river. Make sure you read the race website carefully and confirm what paddling skills will be useful for the event.

If you don’t have those skills, make sure at least a couple of teammates invest the time into training and learning proper paddling skills and safety standards for the conditions. And recognize that taking and passing a skills certification is not the same as consistent practice on the water. You can know the theory behind open-water paddling, but being out in five foot swells and dealing with a capsized boat offshore on day three is very different than practicing in calm conditions with an instructor. Make sure at least a couple of people know what they are doing.

If you don’t have those skills, make sure at least a couple of teammates invest the time into training and learning proper paddling skills and safety standards for the conditions. And recognize that taking and passing a skills certification is not the same as consistent practice on the water. You can know the theory behind open-water paddling, but being out in five foot swells and dealing with a capsized boat offshore on day three is very different than practicing in calm conditions with an instructor. Make sure at least a couple of people know what they are doing.

There are more nuanced and specific questions you might consider -- whose job is it to pick lines on a technical trail? Who brings up the rear? Who is best at route finding through a dense bushwhack? Who watches the clock to facilitate consistent eating and drinking? Who carries the passport or electronic dipper? But what we've outlined above tend to be the eight primary roles distributed across a team of, at most, four people.

What does that mean?

This is what so many of us adore about AR: it’s a team sport. You have to work together. You don’t necessarily have to do ALL of these things individually, but you need to be able to do multiple things well enough to benefit the team, and you need to be ready to step in and adopt someone else’s role when they no longer can handle it. Chances are good, in a multi-day race, that you will have a turn.

What does that mean?

This is what so many of us adore about AR: it’s a team sport. You have to work together. You don’t necessarily have to do ALL of these things individually, but you need to be able to do multiple things well enough to benefit the team, and you need to be ready to step in and adopt someone else’s role when they no longer can handle it. Chances are good, in a multi-day race, that you will have a turn.

For most new expedition race participants, some of the biggest questions - and perhaps fears - arises when contemplating preparation. What does it take to prepare for FIVE days of non-stop racing?!

In this article, we are not going to provide a training plan because such plans are so individualized. Instead, we want to share some thoughts and ideas on how to get started. Once you have processed some of these insights and tips, we urge you to talk to other racers who have experience in training for multi-day events. Feel free to reach out with questions and keep an eye out for follow-up discussions regarding this topic and others in our “New To Expedition Racing” series, to be hosted on Facebook Live!

First, a few things to keep in mind before filling in the training calendar that might help relieve some of the stress. Remember, we have all been where you are before: new to multi-day races, wide eyed over the momentous, unimaginable race you have signed up for, and wondering where to start. One of the most incredible things about AR is that it teaches us that we are capable of so much more than we can imagine, and much of the challenge is mental. This begins with our training.

In this article, we are not going to provide a training plan because such plans are so individualized. Instead, we want to share some thoughts and ideas on how to get started. Once you have processed some of these insights and tips, we urge you to talk to other racers who have experience in training for multi-day events. Feel free to reach out with questions and keep an eye out for follow-up discussions regarding this topic and others in our “New To Expedition Racing” series, to be hosted on Facebook Live!

First, a few things to keep in mind before filling in the training calendar that might help relieve some of the stress. Remember, we have all been where you are before: new to multi-day races, wide eyed over the momentous, unimaginable race you have signed up for, and wondering where to start. One of the most incredible things about AR is that it teaches us that we are capable of so much more than we can imagine, and much of the challenge is mental. This begins with our training.

General Reflections

- Especially as a new racer, you cannot train for day 2, 3, or 5 of a multi-day race. While a handful of truly elite adventure racers have the flexibility in their lives to effectively and safely train 20+ hours a week, most racers, even many of those looking to complete the full course or vie for the podium, are training with far less. People have jobs, families, other commitments, and sometimes they just can’t put in the massive hours that a quick google search might suggest you need to find for a multi-day effort. You and 90 percent of the racers competing in an expedition race are in the same boat, so as always, reach out and ask a more experienced racer for advice on how to make the most of the time you have!

- Much of multi-day racing is mental. That's not to say it's to be easy. You will get tired, your muscles will fatigue, you will be sore. But any seasoned racer knows that finding success in expedition racing largely comes down to mental will, stamina, and fortitude. You will need to put in the time and miles to build a base suited to carry you through, but what will determine whether you complete the race or not is likely more in your head than in the hours you put in this winter. Even the few racers putting in those consistent 20+ hour weeks will be physically taxed as the race unfolds past the first day or two.

|

- Anything counts! Go out for a long hike with friends and families and carry some extra weight (or a baby!). Haul a bike trailer or mount a bike seat to carry your toddler with you for a family adventure. Trade in the car for the bike for an active commute a day or two a week. Squeeze in some strength training in a free Fifteen-minute block. It’s not all about long runs or rides, though those are helpful, too.

- Remember that you will mix up the disciplines. Yes, there will be a long bike ride or two, a seemingly endless trek, or a long day… and night… sitting in a boat, but in adventure racing you are routinely switching the disciplines, giving your body a chance to recover. If the RD tells you to expect 200 miles of biking, remember, this is almost always going to be divided up into at least two stages. So, don’t stress about the cumulative numbers; you’re likely not going to ride 200 miles straight through. Break it down into more manageable bits. What's that cliche about eating an elephant? Bite by bite...

Training Approaches